I recently got access to ChatGPT’s new Study Mode, a feature that offers step-by-step guidance instead of just giving quick answers. As a techie surgeon and educator, I was eager to see how this could help me learn a topic interactively. To test it out, I picked a concept relevant to healthcare that I don’t know well off the top of my head: moral hazard in healthcare. Here’s how my learning session went and some takeaways on using Study Mode—all in first-person, informal style.

Learning a Healthcare Concept with ChatGPT Study Mode

Firing up Study Mode (via the “Study and learn” tool in ChatGPT), I told it I wanted to better understand moral hazard in healthcare. Rather than immediately lecturing, ChatGPT Study Mode started by asking me a few questions about my goals and current understanding, almost like a tutor sizing up a new student. This is is similar to how the tool functions when you use the Deep Research Function. I gave a somewhat rambling answer (honestly, I knew only vague bits about moral hazard from memory). Based on that, it tailored the explanation to my level. I then asked it for “a concise refresher” on the topic. It responded with a clear and compact summary of moral hazard – perfect for getting me oriented.

At this point, I switched to voice mode. Using voice, I dug deeper: “Can you give me a simple example of moral hazard in healthcare that I could use to teach someone else?” ChatGPT obliged with a relatable scenario.

Chat: “Imagine you have a health insurance plan that covers all prescription costs with no copay. When you had a small copay before, you might have chosen a generic drug to save money. But now, with zero out-of-pocket cost, you might always opt for the expensive brand-name drug – even if the cheaper generic works just as well. Why not, if it’s free for you?”

The AI model explained that this increased usage of pricier options, without added health benefit, is a classic case of moral hazard.

It gave another simple example: patients scheduling more doctor visits for minor issues when there’s no copay, whereas they might have skipped unnecessary visits if they had to pay a little each time.

I was impressed by how clearly the AI broke it down. In plain terms, moral hazard in health insurance means that when people aren’t paying the full cost, they tend to use more healthcare (or more expensive healthcare) than they otherwise would. This doesn’t mean patients are acting badly; it’s a natural response to the incentives. As one economics article put it, generous insurance makes healthcare feel “too cheap,” so people consume “too much of it” (like picking the brand-name drug every time if it costs you nothing). The result can be overuse of services or higher costs without better outcomes, which is exactly what insurers worry about.

Next, I asked: “How do insurers use the idea of moral hazard when designing networks or pricing?” This steered the conversation into how insurance companies respond to this behavior. ChatGPT explained that insurers build in “friction” for the consumer – not to deny care, but to make you think twice before overusing low-value care. In practice, this means things like deductibles, copays, and coinsurance (forms of cost-sharing) so you have some skin in the game.

For example, a deductible is the amount you must pay out-of-pocket before insurance kicks in – essentially a built-in threshold that ensures you bear initial costs. If you have a $500 deductible, you’ll likely be more selective about running to the ER for a sniffle, because you pay that first $500 of care yourself. Insurers also create tiered provider networks, offering lower copays or better coverage if you use “preferred” doctors or hospitals that provide cost-effective care. All these tactics are about balancing access and preventing overuse: insurance should cover you when you truly need care, but not make things so free and easy that the system gets overloaded with unnecessary expenses.

I echoed back to ChatGPT my understanding: “So basically, they add a bit of friction for the patient to prevent overutilization – making you pause and decide if that brand-name drug or extra visit is really necessary.”

ChatGPT confirmed: “Exactly. It’s about adding just enough friction so patients (and even providers) make mindful decisions about using healthcare resources, without making care inaccessible.”

I also had it clarify a term – “Can you succinctly define deductible for someone who’s never heard the word?” The answer was packaged nicely and clearly: a deductible is the amount you pay out-of-pocket for healthcare services before your insurance starts covering costs. Once you’ve paid up to that amount, the insurance begins to pay its share. Simple enough!

Throughout this Q&A, Study Mode felt like a cooperative tutor. It prompted me, answered follow-ups, and adjusted explanations based on my questions. This interactive style aligns with Study Mode’s design of guiding learners with Socratic prompts and tailored responses, rather than just handing over an answer key.

From Refresher to Lesson Plan

After this back-and-forth, I wanted to see if ChatGPT could help me turn what I learned into a lesson plan – something I might use to teach others about moral hazard. I asked it to create a “very succinct, easy-to-understand lesson plan for someone learning about moral hazard,” including the key points we had discussed (definitions, how insurers address moral hazard, practical examples) and even a couple of practice problems.

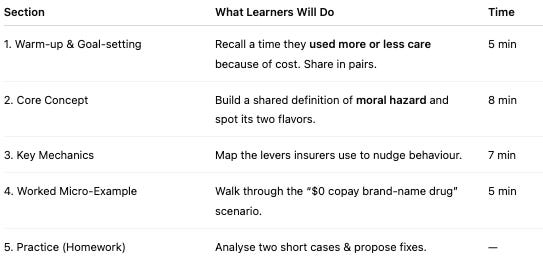

It delivered a neat little outline. To summarize that lesson plan, it included:

Definition & Concept: A plain-language definition of moral hazard in healthcare – essentially that people tend to overuse services when they aren’t paying the full cost themselves.

Key Mechanisms: An explanation of how insurers mitigate moral hazard. This covered cost-sharing tools like deductibles, copays, and coinsurance that ensure patients have some cost responsibility, as well as network incentives (using preferred providers, etc.) to encourage cost-effective choices.

Practical Examples: Relatable scenarios (like our prescription drug example and extra doctor visits example) illustrating moral hazard in action. These examples show why insurers put certain rules in place.

Quick Quiz Questions: One or two simple problems for the learner, to reinforce understanding. For instance, one question asked the reader to consider a scenario (e.g. “If Alice’s insurance removes all copays for doctor visits, how might her behavior change, and why is that an example of moral hazard?”). Another might present a cost-sharing scenario (like “Bob has a $1000 deductible – how could that affect his decision to go to the ER for minor issues?”) so the student can apply the concepts.

(I’ll include the full lesson plan output below for those interested.) Overall, I found this really useful. As someone who might one day teach this topic to colleagues or students, having an outline generated on the fly – which I can then expand on or fact-check – is a huge time saver. It’s like getting a first draft of a teaching prep done in seconds.

Of course, since I’m not an expert on moral hazard myself, I’d still verify details and maybe add nuance (for example, moral hazard isn’t inherently “immoral” – it’s an economics term, and there are also concepts like adverse selection in insurance, though that’s another story). But as a starting point, ChatGPT’s Study Mode provided a solid foundation of knowledge and a structure to pass that knowledge on.

Study Mode Impressions – A Tutor in Your Pocket?

Now that I’ve tried it, how does Study Mode feel compared to a normal ChatGPT session? Study mode feels more purposefully structured to be a personal tutor or study buddy. The mode actively engaged me with questions and checkpoints instead of just responding to my prompts with a long answer. This kept me thinking and involved in the learning process. I can see why OpenAI built it this way – research suggests that active engagement (like answering questions) helps with deeper understanding, and Study Mode is basically ChatGPT nudging you to think, not just absorb answers.

One thing I noticed: the difference between Study Mode and a standard ChatGPT conversation can be subtle at times. In a regular chat, I could still ask follow-up questions and get explanations. But Study Mode formalizes that guiding process. For example, right from the start it asked what I knew and what I aimed to learn, calibrating its teaching style. It also structured information into digestible pieces and even offered to quiz me. In a normal session, ChatGPT might not take that initiative unless prompted. Study Mode essentially adds a layer of “teacher intelligence” on top of the AI’s knowledge base. In my case, that meant a more curated learning journey: starting with basics, then drilling into examples, then zooming out to applications – finally culminating in a lesson plan with review questions. Not bad for an AI I just met!

I’m still exploring this feature and admittedly curious how it might differ with other subjects or longer study sessions. It’s worth noting that you can toggle Study Mode on or off anytime, even mid-conversation, which is nice if you want to switch back to just getting a straightforward answer. In my moral hazard session, I stayed in study mode and it was an organic conversation flow. The voice interaction capability also made it feel very natural – I was literally talking through a concept with an AI tutor. For an educator like me, that spark of interactivity is exciting.

Other Use Cases for ChatGPT’s Study Mode

My experiment was in a healthcare finance concept, but I’m already imagining other ways to use Study Mode day-to-day. Some ideas for clinicians, educators, and anyone curious:

Continuing Medical Education: A clinician could use Study Mode to break down a new medical research paper or guideline. Imagine “studying” a new cancer treatment protocol with ChatGPT prompting you to explain key points, ensuring you truly grasp it rather than just skimming an article.

Academic Study & Exam Prep: Students (or their teachers) might use it for exam reviews. For example, a nursing student could review physiology or pharmacology by having ChatGPT quiz them in Study Mode, or work through practice case studies step by step. It’s like guided 24/7 office hours.

Learning Technical Skills: If you’re learning to code or understand a complex tech concept, Study Mode can walk you through the fundamentals then challenge you with small exercises. For instance, learning a programming language: the AI can teach a concept (loops, algorithms), then ask you to try writing a snippet or predict an output, and give feedback.

General Knowledge & DIY Learning: Really, any topic! You could explore history, economics, or even a new hobby. An educator might use it to generate lesson outlines (like I did) or to get analogy-filled explanations for tough concepts. A curious mind at home might use it to learn personal finance basics – e.g. “Teach me about mortgages” – with the AI ensuring they understand each piece (rates, down payments, etc.) before moving on.

In all these cases, the common thread is active learning. Study Mode shines when you genuinely want to understand something, not just get a quick fact. It’s the difference between cramming an answer and actually learning the material. I plan to keep experimenting with it – I can see myself using it to stay sharp on both tech and health topics.

Bottom Line: My first foray into ChatGPT’s Study Mode was eye-opening. In a short session, I went from zero to a reasonable renewed grasp of moral hazard, had a mini interactive lecture, and walked away with a teaching outline. All from an AI that guided me in a conversational, low-friction way. It feels like having a patient, knowledgeable tutor on call. I’m excited to see how this evolves and how others use it. If you’ve tried Study Mode yourself – whether for a medical topic, an AI concept, or anything else – I’d love to hear how it worked for you and if it made a difference in your understanding.

(Feel free to share your experiences or other use cases in the comments!)

Curious what the lesson plan that ChatGPT spat out looks like? Check it out below!

Mini-Lesson Plan: Moral Hazard in Health Insurance

1 │ Warm-up Prompt

“Think of a service—health-related or not—where you behaved differently once someone else picked up the bill. What changed and why?”

This primes the idea that cost shields change behavior.

2 │ Key Definitions (stick to one sentence each)

Moral Hazard – People or firms use more (or riskier) services after insurance shields them from the full cost.

Ex-ante Moral Hazard – Less effort to stay healthy before coverage (e.g., skipping flu shots).

Ex-post Moral Hazard – Heavier use of care after coverage (e.g., ordering an MRI “just in case”).

Deductible – Up-front amount a member pays each plan year before insurance starts paying.

Copay / Coinsurance – Fixed fee or percentage paid at the point of care to keep “skin in the game.”

Ask learners to rephrase each in their own words (Rule 4: check & reinforce).

3 │ How Insurers Counter Moral Hazard

Lever (adds just-enough friction) How it works Typical Target Cost-sharing (deductibles, copays) Shifts part of the bill to patients Ex-post (patient side) Tiered / narrow networks Lower cost-share at “preferred” providers who deliver value Ex-post (patient & provider) Utilisation review & prior auth Gatekeepers approve only high-value services Ex-post (provider) Value-based payments (bundles, capitation) Clinicians paid for outcomes, not volume Ex-post (provider) Wellness & incentives Premium discounts or rewards for healthy behaviours Ex-ante (patient)

Prompt: “Which lever tackles behaviour before care is needed, and which hit after?”

4 │ Quick Example to Teach With

Scenario: A plan drops all copays for primary-care visits.

Likely ripple: Visits per member rise (some needed, some not). Spending may climb unless early primary-care contact offsets ER or inpatient costs.

Debrief question: “How could the insurer keep visits accessible yet discourage low-value appointments?”

(Hints: tele-triage first, modest virtual-visit fee, appointment availability caps.)

5 │ Homework Problems (no solutions given—designed for discussion)

Generic vs. Brand Game

Facts: Plan A covers generics at $5, brand-name drugs at $35. Next year, Plan B makes both $0.

Tasks:

Predict how prescription patterns change (generic vs. brand mix).

Propose one monetary and one non-monetary tweak Plan B could add to curb low-value brand use without hurting access.

“Back-Up” MRI

Facts: An orthopedic clinic is in a fee-for-service contract that pays per imaging study. The payer sees MRI volume 40 % above peers.

Tasks:

Identify the moral-hazard driver from the provider’s perspective.

Outline a value-based contract term that could realign incentives.

List a patient-facing strategy that might also reduce unnecessary MRIs.

Encourage learners to justify answers with one-sentence reasoning—keep it concise.

Quick Exit Ticket

“In one line, explain why moral hazard is about behaviour, not bad morals.”

Collect two or three responses to reinforce the core takeaway.