Operator’s Guide: Enrolling in Medicare Part B for CMS’s ACCESS Model

The CMS ACCESS Model Requires Participants to be Providers

This is Part 8 of a 12-part Techy Surgeon operator series on the CMS ACCESS Model. To navigate this series start to finish, check the archives if you’re a subscriber or check out this page on Techy Policy.

Building for ACCESS? RevelAi Health helps virtual care and digital health teams stand up the AI-powered care coordination and mandatory reporting infrastructure required to operate in models like ACCESS. We augments value-based healthcare operations for care organizations with responsible AI and automation so you can focus on clinical care, not checkboxes.

→ Book a demo: Here | Contact us by email: Here

A Quick Personal note

Many digital health companies considering the CMS ACCESS Model are intimidated by the idea of becoming a Medicare Part B provider. The bureaucracy feels foreign, the acronyms overwhelming, and the stakes high. I wanted to demystify that process.

I have some personal experience here. For over 30 years, my father ran a private practice primary care clinic in South Texas, a true mom-and-pop operation. My mother was the office manager, and from time to time my brothers and I would work reception or shadow him on patient rounds. Years later, during my orthopedic trauma fellowship, I helped him sell the practice to an accountable care organization. I remember spending hours over the years helping my mom reset her PECOS password and troubleshoot the first wave of MIPS reporting. Setting up the first electronic health record with them was absolute hell, and by the time my father sold the practice my mother was severely burned out from the administrative burden of maintaining the practice. Though it’s been many years since I last navigated these systems directly, those memories informed my research for this guide.

I put this playbook together by poring through the CMS website and consolidating what I learned into a practical reference augmented by GPT Deep Research grounded in documents from CMS in a project folder. If there are others out there with more recent or hands-on experience with Part B provider enrollment, I welcome your input—please reach out. I hope that becoming a Part B provider does not become a barrier for digital health companies and virtual care providers that have otherwise excellent platforms and could serve an expanded population of patients through this program.

Overview: This playbook provides a practical, step-by-step guide for digital health companies (especially virtual-first or early-stage startups) to become Medicare Part B–enrolled organizations eligible for the CMS Advancing Chronic Care with Effective, Scalable Solutions (ACCESS) model. We explain what Part B enrollment means, how to navigate the PECOS enrollment process, and how to meet the requirements of the ACCESS model. Throughout, we clarify common misunderstandings and outline responsibilities, costs, and pitfalls, all in plain language for health tech founders and operators.

This is a long article, if this much text burns your eyeballs, I created a visually friendly primer on the Techy Policy website that is publicly accessible. You can find it here.

1. Medicare Part B Enrollment 101: What It Means and Why It Matters

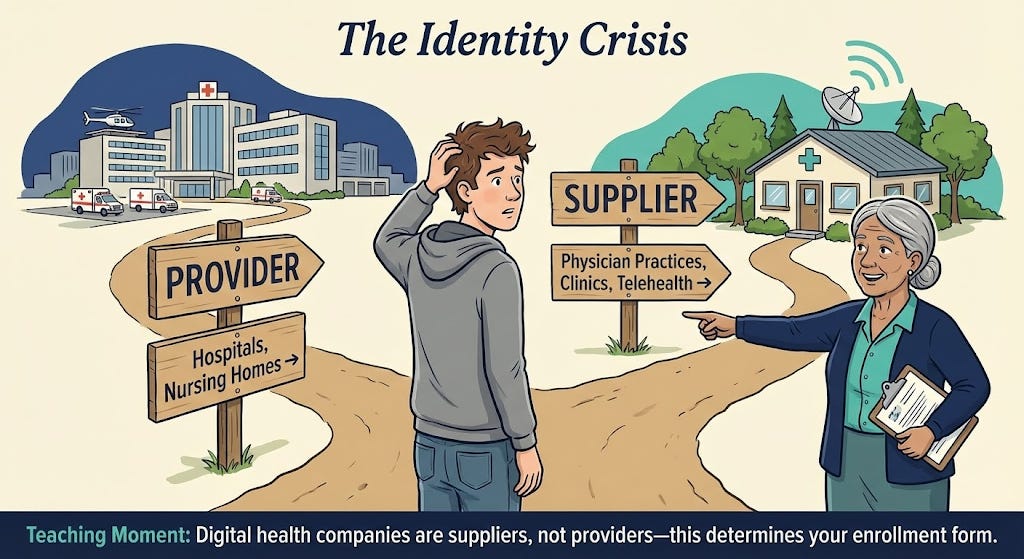

What is a Medicare Part B–enrolled provider/supplier? In Medicare terminology, providers typically refer to institutions (like hospitals) and suppliers refer to individuals or entities that furnish Part B medical services (e.g. physician practices, clinics)[1]. For our purposes, being Medicare Part B–enrolled means your organization (e.g. your virtual clinic or medical group) is officially registered with Medicare to provide covered services to Medicare beneficiaries and bill Medicare Part B for payment. Essentially, you’re on Medicare’s list of approved health care entities.

Who is eligible to enroll? Generally, any individual practitioner (physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, etc.) or group practice that meets licensing requirements can enroll in Medicare Part B. Digital health startups usually establish a medical group or clinic (with clinicians on staff) to deliver care – that entity can enroll as a “clinic/group practice” supplier. You’ll need at least one licensed Medicare-eligible clinician (e.g. an MD/DO or certain non-physician practitioners) associated with your organization to serve as the enrolling provider. In fact, the ACCESS model requires participants to designate a physician Clinical Director and ensure all clinicians delivering care are individually Medicare-enrolled and affiliated with the organization[2][3]. If you’re a pure software company, you’ll likely need to partner with or hire medical providers and form a clinical entity to enroll.

Key obligations of Medicare-enrolled entities: Enrolling in Medicare is like entering a regulated contract with the federal government. Some core commitments and responsibilities include:

Follow Medicare rules and regulations: You must comply with Medicare coverage policies, coding and billing rules, and all relevant federal laws (like HIPAA for patient privacy and security). You are subject to oversight by CMS and its contractors. For example, you can only bill for medically necessary services and must adhere to documentation requirements.

Maintain state licensure & scope of practice: All clinicians must have valid licenses in the states where patients are treated (for telehealth, see Section 4 on virtual practice). Services must be delivered within each provider’s scope of practice under state law. The organization itself may need to register as a professional corporation/clinic per state requirements. CMS also requires that participants meet all applicable federal and state requirements (licensure, certification, etc.)[2].

Medicare “participating” status: Upon enrollment, you’ll choose whether to be a participating provider. Participating providers agree to accept Medicare’s approved amount as full payment for services (Medicare pays 80% and patient/secondary pays 20%) – this is highly recommended for ACCESS participants. You’ll typically sign the Medicare Participating Physician or Supplier Agreement (Form CMS-460) during enrollment to formalize this. Being “participating” simplifies billing and means you can’t charge patients above the Medicare fee schedule rate[4]. (Non-participating providers receive slightly lower reimbursements and can balance-bill limited amounts, but that model is not ideal for building a patient-friendly digital health service.)

Billing under Medicare Part B: Once enrolled, you can bill Medicare for covered services under the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS). Medicare will issue your organization a billing number (often called a PTAN) linked to your National Provider Identifier (NPI). You’ll submit claims and receive payments via your regional Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC). More on billing and the PFS in Section 3.

Update information and revalidate: Medicare enrollment isn’t “set and forget.” You must keep your enrollment information current. Changes in ownership, practice location, or legal status must be reported within 30 days; other changes (phone number, managing personnel, etc.) within 90 days[5]. Moreover, Medicare requires revalidation of your enrollment typically every 5 years (for most Part B suppliers) – a process of re-submitting and confirming your info. Failure to update changes or respond to revalidation can result in billing privileges being revoked[6].

Program integrity and screening: When you apply and periodically thereafter, you and your key owners/managers will undergo background screening. Any individual with certain felonies or exclusions from federal health programs can cause denial. You must also disclose any adverse legal actions (like malpractice suits or license discipline) on your application. Honesty is critical; nondisclosure is a common pitfall that leads to denial.

Accepting all patients? Unlike some value-based programs, Medicare enrollment does not obligate you to take every Medicare patient. You retain control over where and how to market or limit your services. However, you cannot discriminate based on things like race, religion, or health status, and if you do treat a Medicare beneficiary you must abide by Medicare coverage and billing rules. ACCESS participants specifically will be listed on a public CMS directory, and patients or referring providers may seek you out[7][8]. Being enrolled means you’re “open for business” to Medicare beneficiaries under the conditions you define (e.g. treating only certain chronic conditions under the model).

Why Part B enrollment is required for ACCESS: The ACCESS model is a Medicare initiative that pays for technology-enabled chronic care. CMS explicitly states that to participate, an organization “must be enrolled in Medicare Part B as [a] provider or supplier”[9]. This is non-negotiable – CMS will not waive the enrollment requirement even for innovative startups[10]. Enrolling in Part B establishes the necessary billing framework (e.g. you’ll use your Medicare enrollment to submit the model’s G-codes for payment). It also subjects you to Medicare’s oversight, which gives CMS confidence in your reliability and compliance. In short, Part B enrollment is the gateway to receiving Medicare payments, whether traditional fee-for-service or the new ACCESS payments.

2. Step-by-Step: Enrolling via PECOS (Provider Enrollment Chain & Ownership System)

Medicare provider enrollment can seem daunting, but CMS’s online system PECOS streamlines the process. PECOS lets you submit your application electronically and is faster than paper (often 2–4 weeks faster)[11][12]. Below, we walk through the enrollment process for a virtual-first group practice – from preparation to approval – with emphasis on the elements relevant to digital health startups.

2.1 Prepare Required Information and Documents

Before logging into PECOS, gather all necessary data and documents. Missing pieces are a leading cause of delays or denials. Use this checklist:

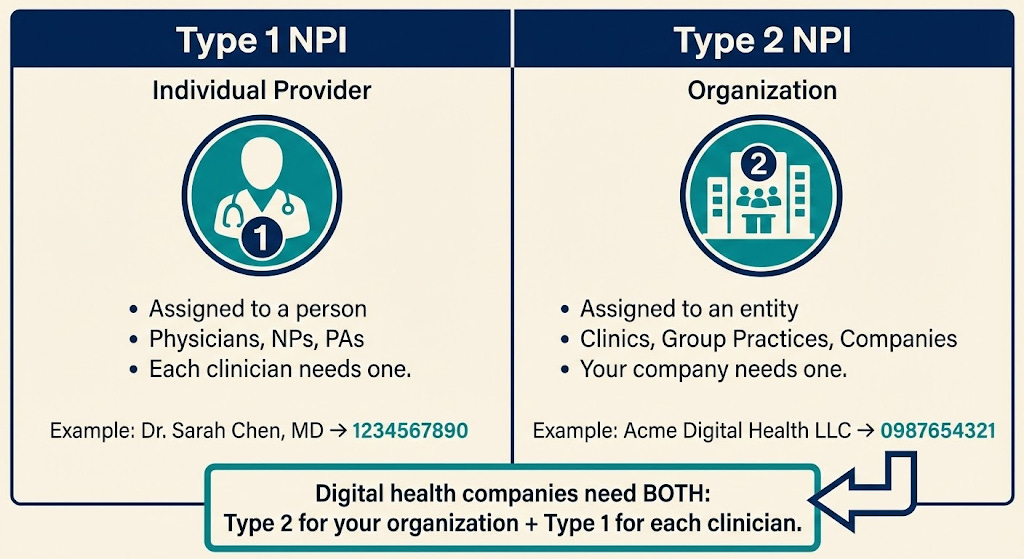

National Provider Identifiers (NPIs): You’ll need a Type 2 NPI for your organization (if you don’t have one, obtain one from the NPPES website first)[13]. Also have the Type 1 NPIs for any individual clinicians who will reassign billing to your group (or ensure they’ve applied for theirs).

Legal business info: Exactly as registered with the IRS. This includes your legal business name, Tax Identification Number (TIN) or EIN, business type (e.g. LLC, C-Corp, PC), and the date of incorporation/formation. It’s critical that the name and TIN match IRS records (CMS will likely verify using an IRS database). A copy of the IRS EIN assignment letter (Form SS4 confirmation) is useful to upload as proof.

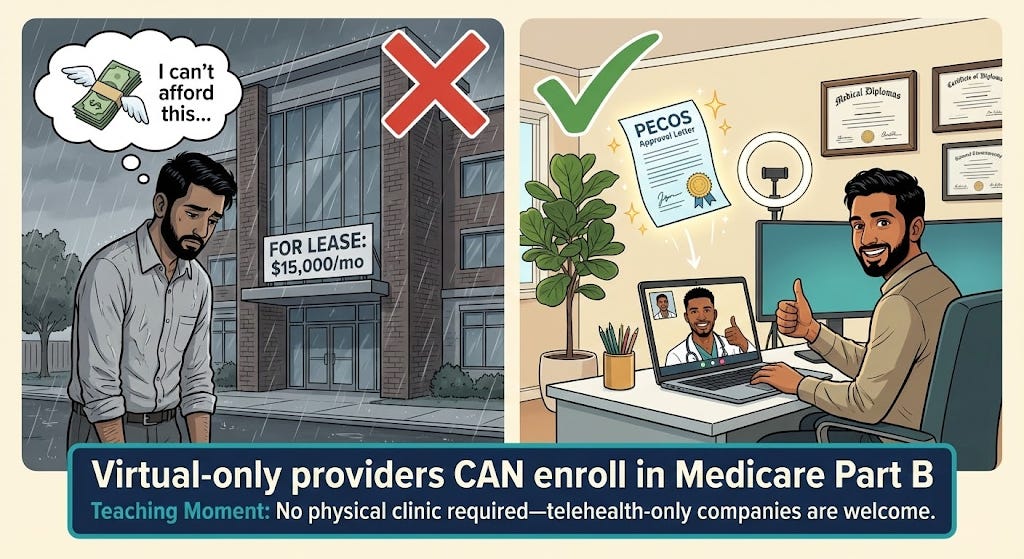

Practice location and contact info: An official practice location address is required, even if you operate virtually. This cannot be a P.O. box – use a physical address (e.g. your company’s office, your clinic’s headquarters, or one clinician’s office). If you have no physical clinic whatsoever, you may list a professional’s home office or your corporate address and designate it as a “Telehealth/Administrative Only” location[14][15]. (CMS now allows telehealth providers to enroll with a home or virtual address flagged as non-public[16][17].) You’ll also provide a billing address and phone (for correspondence and remittances). These can be the same or different from the practice address.

Licenses and certifications: For each clinician, have copies of their state professional licenses (e.g. medical license, NP license) ready to upload. Ensure licenses are active in the states you plan to serve. If your organization needs any facility license or registration in your state, have that as well.

Ownership and management details: You must disclose all owners (5% or greater ownership) as well as managing individuals (like Officers, Directors, LLC Managing Members) in the application. For each such person, gather their legal name, SSN, date of birth, position, and home address. Any organizational owners (e.g. a parent company) also need to be disclosed with FEIN. If you’re venture-backed, note that any entity with 5%+ ownership (direct or indirect) will be listed. Ensure these stakeholders are aware and provide you the info. Tip: If your state’s corporate practice of medicine laws require the clinic to be physician-owned, your ownership structure might reflect that (e.g. a MD holds shares in a PC). In PECOS, you’d list that physician as an owner accordingly.

Billing agent or delegated official (if any): If you plan to have a specific person (like a COO or a consultant) handle enrollment or sign forms on behalf of the organization, determine if they need to be added as an Authorized Official (AO) or Delegated Official (DO). Typically, an Authorized Official is an officer/owner with authority to sign legal agreements (often a CEO, COO, or physician-owner), and they must sign the initial enrollment. A Delegated Official can be designated to make updates later. Make sure these individuals have or create PECOS login accounts (more on that next).

Bank account for payments: Medicare payments are electronically deposited. Prepare your Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) details – the bank name, routing number, and account number for the account where you want Medicare funds. You’ll fill out or upload CMS Form 588 (EFT Authorization) as part of enrollment[18][19]. A voided check or bank letter may be submitted to verify account details.

Supporting documentation: Scan PDFs of key documents: IRS EIN letter, business incorporation documents (optional, usually not required but good to have), voided check for EFT, CMS-460 (participation agreement) if signing on paper, any local business licenses, etc. Also, if any owner or practitioner had prior adverse actions (sanctions, felonies), prepare written explanations and copies of resolution documents to upload.

Having these ready will make the online process smoother. A quick pre-flight check: your NPI registry entry for the organization should reflect the correct name and address (NPPES data should align with what you’ll put in PECOS to avoid identity mismatches).

2.2 Create PECOS Login and Access (I&A System)

PECOS uses the CMS Identity & Access (I&A) management system for secure logins. If you’ve never used CMS systems:

Register for an I&A account: Go to the PECOS login page and select “New User? Register Here.” This will lead you to the CMS I&A portal. Typically, if you as an individual already have an NPI, you may have a username from NPPES – those credentials can work for PECOS. Otherwise, create a new account by providing your personal information. During registration, you’ll designate whether you’re acting as an individual provider, an organizational provider, or a staff for an organization.

Connect to the organization’s TIN: In I&A, after your account is created, you may need to establish a connection to your organization’s tax ID if you are enrolling an entity. This involves adding the organization’s EIN under your account (as an “Employer” connection) so that PECOS knows you are authorized to act for that entity[20][21]. If you are the business owner or an executive, you should register as an Authorized Official (AO) of the entity in I&A. This will typically require verification (often you can self-declare if you’re the one creating the record, and the system may validate the EIN).

Add any other users (optional): Through I&A, you can invite additional users – for example, if your head of operations will also work on the enrollment, you can set them up as a Delegated Official or staff, linking them to the organization’s TIN. Only AOs can submit the final application, but delegated users can help fill it out. Ensure each person uses their own account (sharing logins is not allowed).

Once your I&A setup is done and you have the proper access to the organization’s enrollment, you’re ready to use PECOS. (If this is confusing, note that CMS provides “Enrollment on Demand” video tutorials on I&A and PECOS – they can be helpful[22][23].)

2.3 Start a New Enrollment in PECOS

Log in to PECOS with your I&A credentials. You’ll arrive at the PECOS dashboard. Here’s how to initiate the application:

Select “My Enrollments”: On the welcome screen or main menu, click the “My Enrollments” button to manage enrollments associated with your account. This will show any existing records. If your organization is new to Medicare, it likely won’t have any record yet. You should see an option to “Create Initial Enrollment Application.” (If enrolling yourself individually, you might see your name under enrollments; for an organization, you might see the org name if an EIN connection exists.)

Choose provider type/application: PECOS will guide you through a sequence of questions to determine the correct enrollment form. For a digital health group, you will likely select an option indicating you are enrolling as a “Clinic/Group Practice” (CMS-855B form) rather than an individual practitioner[24][25]. PECOS automatically picks the right form based on your inputs. Indicate this is an initial enrollment (not a change or revalidation). If asked for a practice specialty or type, choose the one that best fits (many digital clinics use “Multi-Specialty Group” if they have various clinicians, or a specific clinic type like “Clinic/Center – Telehealth” if available).

Application fee prompt: Part of the initial questions may touch on application fees. Good news: Physician and non-physician practitioner organizations are exempt from the CMS enrollment fee[26]. Medicare charges a hefty application fee (over $700 in 2024) to institutional providers (hospitals, home health agencies, etc.), but physician practices do not pay this fee[26]. If PECOS asks for payment, double-check that you correctly indicated the provider type. You should not be prompted for a fee when enrolling a physician-owned clinic or group practice. (If you somehow are, contact your MAC for clarification or see if an incorrect category was selected.)

Now you’ve begun the actual enrollment form. The system will present a series of sections (often called “topics”) to complete. PECOS is scenario-driven – some sections appear or skip based on previous answers. Save as you go, and note you can exit and return later (PECOS saves partially completed apps).

2.4 Provide Organization Information

You will enter the core details about your company/clinic:

Basic Identifying Info: Input the Legal Business Name of the organization exactly as it appears on IRS documents (including punctuation or abbreviations). Enter the EIN (or SSN if sole proprietor). Select your entity type (corporation, LLC, partnership, sole proprietor, etc.). Many digital health startups form a professional corporation or LLC for the clinical entity – ensure you select accordingly. You may also be asked for a D/B/A name (doing-business-as) if applicable (e.g. “XYZ Health” if that’s a trade name different from the legal name).

Taxonomy and specialty: You might need to choose the organization’s taxonomy code or describe the specialty. For example, “Clinic/Center – Multi-Specialty” or “Internal Medicine Group” or similar. This is for classification; it doesn’t limit what you can do but should reflect your scope (if primarily mental health, choose that, if multi-condition, multi-specialty is safe).

Practice Location: Here, add the primary practice location address. As noted, this can be your virtual office. If using a home or non-public address (because you have no clinic), mark it as “Private Practice Office for Telehealth/Administration” (PECOS has a checkbox for designating a location as home/telehealth so it won’t be publicly listed)[16][17]. If you have multiple sites (e.g. perhaps an HQ in one state and a clinical branch in another), you can add additional practice locations. However, if you’re fully virtual, typically one primary location (even if just an administrative office) is sufficient. Medicare assigns your servicing MAC region based on this address. Note: If you plan to treat patients in multiple states, you do not necessarily need multiple enrollments or addresses – one enrollment can cover multi-state operations if your providers are licensed appropriately. But check with your MAC if in doubt; sometimes a MAC may want an enrollment per state if there are different practice entities.

Phone and email: Provide a business phone number for inquiries and a contact email. CMS and MACs often use email for communication, so use one that is monitored (e.g. compliance@yourcompany or an individual’s email). You will also specify if the mailing address for Medicare correspondence is the same as the practice address – if not, provide a mailing address (could be a P.O. box or office). For virtual groups, you might list your corporate mailing address here if different from a clinician’s location.

Special Payment address: PECOS will ask where payments and remittance notices should be sent (this correlates to the old concept of where paper checks/EOBs go). Since Medicare pays electronically, this is mostly for record. You can use your billing office address or same as mailing. Many startups just repeat their main address. Ensure you complete the Electronic Funds Transfer info as well (you might have to upload the CMS-588 EFT form or input banking details in a financial section).

Medical records storage: Some forms ask where medical records will be stored if different from practice location. If you host records electronically (e.g. in a cloud EHR), you can list your main address or the address of the custodian (often same office). This is about where records would be available for audit.

Throughout, consistency is key: Double-check that the organization name, TIN/EIN, addresses, etc., match across all sections and match supporting documents. Even a minor typo (like “Street” vs “St.” or an extra space in the name) can trigger verification hiccups.

2.5 List Owners, Directors, and Key Personnel

Next, PECOS will prompt for “Ownership Interest and/or Managing Control” information. This is where you disclose who is behind the organization:

Owners: Enter each individual or entity with 5% or greater direct or indirect ownership. For each, provide their name, SSN/EIN, date of birth (if individual), address, and ownership percentage. If an owner is another company, you’ll need that company’s EIN and legal name. You may need to drill down owners of parent entities until all 5%+ owners are reported (for VC funds, this might not be required if no single LP owns 5%; usually just list the fund itself if it owns >5%). If you (the founder) own 100%, this part is straightforward – you list yourself. If you have co-founders or a cap table, list all accordingly.

Managing control (Managing Employee/Director): If there are people who don’t own shares but have controlling roles (CEO, COO, President, Medical Director, etc.), list them as managing employees. Typically the Medical Director (physician lead) should be listed here if they aren’t an owner – CMS requires an ACCESS participant to “designate and maintain a Medicare-enrolled physician as Medical Director responsible for oversight of care”[27], so that person should appear as a managing employee in PECOS. Provide their personal details (SSN, DOB, title, address). For a small startup, many individuals may be both owners and managing employees (e.g. a physician-founder who is 50% owner and also medical director – you might list them under both categories in PECOS).

Authorized and Delegated Officials: The system will identify or ask who the Authorized Official (AO) is – this should be an executive/owner who can legally bind the company (often the CEO or an MD president of the clinic). This person will sign the application. You can also specify Delegated Officials (DO) now or later – people who can communicate with Medicare on your behalf. Only an AO can appoint a DO. A Delegated Official might be your operations lead or billing manager who will handle updates. Make sure these individuals had I&A accounts set up as noted. The AO must be listed as having a managing control or ownership role in the section above for the system to allow them as AO.

When entering people, PECOS may cross-check some info (like making sure an SSN is valid, etc.). Fill everything accurately. There will be a series of yes/no questions for each person about convictions, exclusions, etc. Answer these truthfully for each owner/manager (e.g. have they ever been convicted of a felony, excluded by OIG, had a license revoked, etc.). Typically for a new startup, these are “No” – but ensure you have asked the individuals. If any “Yes,” provide explanations and upload documentation.

2.6 Reassigning Practitioner Benefits to Your Organization

One critical step for group enrollment is linking your individual clinicians to the new group so that their services can be billed under the group’s Medicare billing number. Medicare does this via “reassignment of benefits.”

Ensure individual enrollment: Each practitioner (doctor, NP, PA, etc.) who will care for Medicare patients in your model must be enrolled in Medicare themselves. If you have hired clinicians who have never enrolled in Medicare, they will each need to submit a CMS-855I enrollment (or use PECOS for individual enrollment) in parallel. They can enroll as individuals and indicate they will reassign benefits to your group. Alternatively, some MACs allow you to file the group (855B) and individual (855I) applications simultaneously and link them. In any case, your clinicians need to be in Medicare’s system. (If they’re coming from other practices where they were enrolled, they just need to add a reassignment to your group – see next.)

Add reassignments (CMS-855R): PECOS should present a section for “Reassignment of Benefits”. This is essentially CMS-855R within the online app. Here you will add each practitioner’s NPI who will reassign their billing to your organization’s TIN. The system may let you search by NPI or name to pull up the individual’s record. If the provider is already enrolled (say they worked elsewhere), their profile will be found and they can be linked. If they’re new and concurrently applying, you might not find them yet – in that case, you can submit their reassignment later, or coordinate with your MAC. Ideally, have each clinician enroll first (855I), then once they get their Medicare PTAN, add them to your group (855R). However, to get started, you can include the reassignment section to list your known providers.

Clinician details: For each reassigned provider, you’ll provide their personal info and confirm that they will reassign payment to your group. The provider themselves may need to log in to PECOS to approve the reassignment, or they can sign a paper CMS-855R and you keep it on file. PECOS often handles this via electronic signature requests. Essentially, by reassigning, the clinician agrees that your entity can bill and receive Medicare payments for services they render. The ACCESS model explicitly requires that all practitioners “have reassigned their Medicare billing rights to the participating TIN” (your organization)[3], so this step is mandatory.

Medical Director as practitioner: If your Medical/Clinical Director will also see patients (likely yes), they too must reassign to the group. If they are a physician who founded the group, they might be both an owner and a reassigned provider.

Make sure to submit and maintain an up-to-date roster of all Medicare-enrolled practitioners (with NPIs) under your TIN[28]. In practice, this means keeping your PECOS enrollment updated if you add or remove clinicians over time. For initial enrollment, list everyone you plan to involve from Day 1.

2.7 Final Steps: Attach Documents, Review, and Submit

As you complete each section of the application, PECOS will mark them complete. Before finishing, you’ll go through these final parts:

Required document uploads: PECOS will generate a list of required supporting documents based on your application. Common uploads include: IRS document (to verify TIN/legal name), EFT authorization (CMS-588 form), voided check or bank letter, copies of professional licenses for each practitioner, and potentially the CMS-460 (participation agreement) if you indicated you’ll be a participating provider (if not done electronically). It’s often a good idea to also upload a cover letter explaining any special circumstances (for example, if you have no physical site and are listing a home address, state that it’s a telehealth-only practice address to avoid confusion). Upload all relevant files in the categories provided. PECOS allows PDF or image files for each required category.

Medicare Participating Agreement (CMS-460): PECOS may include a step where you choose to accept Medicare’s allowed charge as payment in full (i.e. become a participating provider). If you select yes, you are agreeing to submit the CMS-460 form within 90 days. Some PECOS flows let you electronically sign this as part of the submission. Otherwise, you can download CMS-460, sign it, and upload or mail it to your MAC. Given your likely desire to fully participate in ACCESS, check “Yes” to being a participating provider. This ensures your startup will be listed as accepting Medicare assignment (which is usually expected in these models).

Final review: Thoroughly review a compiled summary of your application. Double-check every field. Ensure addresses are correct, NPIs are correct, and no section is missing. Accuracy is crucial – as one Medicare enrollment advisor put it, “If you get it right the first time, you are in the clear... mess up just once and you immediately delay the process by 3 months”[29][30]. Common mistakes to catch: typos in names/IDs, forgetting a required owner, inconsistent addresses, or missing documents.

Electronic signature & submission: When satisfied, proceed to electronically sign the application. The system will typically have the Authorized Official (you) digitally sign a certification statement. By signing, you legally attest that all information is truthful and complete. Submit the application through PECOS. You should get a tracking ID (a numeric Application ID) and a confirmation notice on screen or via email.

PECOS submissions are transmitted to your regional Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) for processing. You can monitor application status by logging into PECOS and checking My Enrollments (it will show statuses like “In Progress,” “Pending Review,” etc.), or use the Enrollment Status Lookup on your MAC’s website.

2.8 After Submission: MAC Communication and Approval

Once submitted, be responsive to any MAC requests. A Medicare contractor enrollment analyst will review your application:

Additional documentation or corrections: The MAC might contact you (via the contact person email/phone you provided) to clarify information or request missing items. For example, they might ask for a copy of an ID, a business license, or to correct a date. Respond promptly and thoroughly – you usually have a limited window (often 30 days) to reply, or the application could be rejected.

Site visit: For new enrollments, CMS may perform an unannounced site visit as part of screening (this is more common for certain suppliers, but physician practices can be visited too). If you have an office, ensure signage and someone present during business hours. If you listed a home, be prepared to explain your virtual practice if a contractor comes. This is part of program integrity screening.

Approval notification: If all is in order, the MAC will approve the enrollment. You will receive an approval letter (sometimes via postal mail, sometimes electronically). This letter will contain your organization’s Medicare Provider Number/PTAN and the effective date of enrollment. Typically, the effective date is retroactive to the date the MAC received your complete application. From that date onward, you can bill Medicare for services. Keep this approval letter for your records.

Congratulations – you’re enrolled! Your digital health company is now a Medicare Part B supplier. You will appear in Medicare’s Provider Enrollment Chain and Ownership System as an active entity. This means you can not only bill regular fee-for-service if needed, but you’re also eligible to sign a participation agreement for the ACCESS model with CMS (since being an enrolled provider is a prerequisite)[31].

Working with your MAC: After approval, establish contact with your MAC’s provider enrollment department if you have questions. Also set up an account on your MAC’s provider portal if available. You’ll send any Part B claims to this MAC and interact with them for payment issues. Section 5 discusses billing setup in more detail.

Before diving into ACCESS specifics, a brief primer on Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule – since understanding the traditional payment system will help clarify how ACCESS changes things.

3. Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Basics for a New Provider

Medicare Part B primarily pays for services under the Physician Fee Schedule (PFS), which is essentially a catalog of services and payment rates. Here’s what a Part B supplier (like your new organization) should know:

CPT/HCPCS Codes: Every billable service has a code (e.g. a visit, a lab test, a telehealth consult). Under PFS, you submit claims with these codes and Medicare pays the pre-set amount for each (adjusted by region). For example, a 30-minute outpatient visit might be CPT 99203, which has a certain dollar rate in the fee schedule.

Supplier billing under PFS: As a Medicare-enrolled supplier, you’ll use your clinicians’ NPIs and your group NPI/TIN to submit claims for any Part B services you provide. Payment is typically 80% from Medicare (since patients have a 20% coinsurance, unless they have supplemental insurance or you waive it in certain model contexts). Being a supplier means you agree to abide by these set fees (especially if participating). You cannot arbitrarily set prices for Medicare patients – it’s all governed by the PFS.

Updates and geographic variation: The PFS is updated annually (with new codes, changed values) by CMS. Payment rates vary by location due to Geographic Practice Cost Indices (GPCIs). If you’re in a high-cost area, the fees are slightly higher. Your MAC will handle these adjustments. You don’t need to calculate them, but be aware that the practice location you listed will determine your base rates.

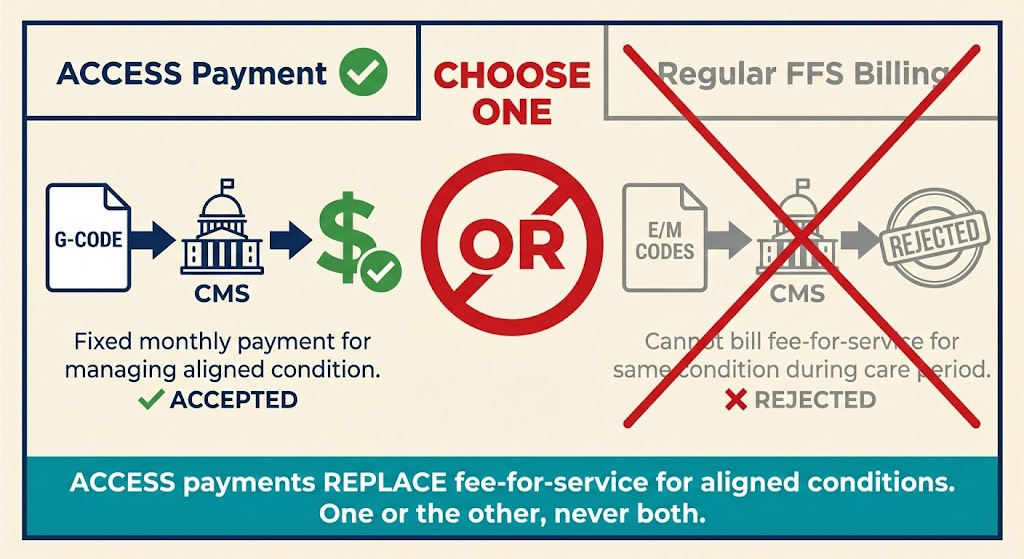

Why PFS matters for ACCESS: The ACCESS model introduces an alternative payment – Outcome-Aligned Payments (OAPs) – which are fixed, periodic payments tied to patient outcomes rather than specific services[32]. In essence, ACCESS “replaces traditional fee-for-service billing with fixed recurring payments” for participants[32]. However, these payments are implemented through the existing claims system using special HCPCS G-codes (more on that in Section 5). So your familiarity with coding and claims still matters. Moreover, while an ACCESS patient’s chronic care is covered by the model payment (meaning you generally “may not bill any Medicare FFS claims” for those patients’ aligned condition during the ACCESS care period[33]), there may be scenarios where you or others still bill the PFS (e.g. services outside the model’s scope or by other providers). You need to understand those boundaries to avoid double billing.

Non-ACCESS services: If your organization provides any services outside of the ACCESS model (for instance, if you occasionally see a Medicare patient for a standard acute visit or offer services not covered by the model), you would bill those normally under the PFS. Joining the model doesn’t prevent you from billing FFS for unrelated services or for patients not in an active care period.

In summary, the PFS is the default Medicare payment method. ACCESS is testing a new method (outcomes payments) on top of the Part B framework. Your enrollment allows you to bill under PFS, and CMS will leverage that enrollment to pay you the model’s fixed fees (via codes). Being knowledgeable about PFS ensures you comply with rules like “no double billing” – i.e., if you’re getting a monthly ACCESS payment for managing a patient’s diabetes, you should not also submit a standard E/M office visit claim for routine check-ins for that patient’s diabetes during the same period[33]. The model’s payment is instead of those visit payments.

One more concept: coordinating providers. ACCESS allows patients to keep seeing their primary care providers or specialists. Those outside providers can bill Medicare as usual. In fact, ACCESS introduces a small co-management fee payable to patients’ primary care doctors for collaborating (about $100/year per patient)[34][35]. That co-management payment is billed under a specific code (likely a G-code) with no cost-sharing. This underscores that traditional Medicare billing and the model-specific billing will coexist, and you’ll need to use both appropriately. We’ll cover those codes next, along with your responsibilities as a newly enrolled entity.

4. Common Misconceptions – Clarified

Stepping into Medicare can be confusing, and digital health startups often hear conflicting information. Let’s clear up a few common misunderstandings relevant to virtual-first providers and the ACCESS model:

“We need a physical clinic to enroll in Medicare.” – False. Medicare does not require a brick-and-mortar clinic. Virtual providers can absolutely enroll. As long as you have a valid business address (even if it’s a home office or shared workspace) and your clinicians are properly licensed, you can become a Part B provider[15][17]. CMS has made permanent policies to accommodate telehealth practices. For example, if your only practice location is a physician’s home address (because all services are via telehealth), you can list that and mark it as “Administrative/Telehealth Only”[16][17]. Medicare will enroll you and simply not publish the home address publicly. In ACCESS, many participants are expected to be virtual care companies[36][37]. So, don’t let lack of a clinic stop you from enrolling. Just be transparent in your application about your telehealth setup (as described in Section 2).

“We’re a software/digital therapeutics company, not a provider – can we enroll?” – Yes, if you establish a clinical entity. Medicare enrollment is for organizations that furnish healthcare services. A pure software vendor can’t enroll, but a software company that hires or contracts clinicians to deliver care can (e.g. your digital therapeutic is used under a clinician’s oversight as part of a treatment plan). In ACCESS, CMS expects many “technology-enabled care organizations” will formalize as Medicare providers[36][38]. You might need to create a subsidiary medical group or partner with a medical group for the actual enrollment. In any case, the entity that contracts with CMS for ACCESS must have Part B billing status. This may require aligning with physicians (for instance, via a friendly PC model if you’re in a state with corporate practice of medicine restrictions).

“ACCESS is an innovation model, so normal Medicare rules don’t apply.” – False. While ACCESS offers new payment methods and flexibility, participants remain Medicare providers and must follow all baseline rules unless explicitly waived. That includes privacy laws (HIPAA), patient rights, civil rights/non-discrimination, and Medicare’s fraud and abuse laws (Stark Law, Anti-Kickback Statute, etc.) to the extent they apply. CMS is clear that participants must meet all federal and state requirements as any provider would[2]. The model does waive certain payment rules (for example, it pays for services in a bundle rather than itemized), but it doesn’t exempt you from oversight. Think of it as operating within Medicare, just under a special payment arrangement.

“During an ACCESS care period, we can still bill some fee-for-service if needed.” – Mostly false. When a patient is “aligned” to your ACCESS program for a specific condition, you and your affiliated clinicians cannot bill regular Part B fee-for-service claims for managing that condition during the active care period[33]. The intent is that the Outcome-Aligned Payments replace FFS for that scope of care. For example, if you’re managing a patient’s hypertension under ACCESS, you wouldn’t bill separate E/M visits or remote monitoring codes for hypertension – all those activities are wrapped into the one periodic payment. The McDermott+ policy brief summarizes: “ACCESS participants and affiliated entities may not bill any Medicare FFS claims for aligned beneficiaries during active care periods”[33]. If you do, those claims won’t be paid (or will be recouped) because CMS doesn’t pay twice. However, this doesn’t stop other providers from billing (e.g. if the patient goes to an unaffiliated specialist, they bill normally). And if the patient needs care beyond your model’s scope, those can still be billed (for instance, you manage their diabetes in ACCESS but they break a leg and an orthopedist treats it – that orthopedist bills Medicare as usual). The model defines what counts as overlapping. As a participant, you’ll need to understand these rules to avoid improper billing. Generally, think: ACCESS payment covers all your services for the targeted condition, so you won’t submit typical CPT codes for those services while the patient is in the program.

“If we join ACCESS, we have to treat all Medicare patients.” – No. Participation in an Innovation Model is voluntary for providers and patients. You can define your scope (the chronic conditions you focus on, the capacity you have, etc.). Patients have to choose to enroll with you for ACCESS, or be referred and consent[7][39]. You’re not suddenly on the hook to accept every Medicare beneficiary who knocks on your door. That said, CMS will list participants in a directory and you may get inquiries. It’s good practice (and possibly a condition of the model agreement) not to cherry-pick patients in a discriminatory way. But you can limit enrollment based on your clinical focus (e.g. only patients with the specific chronic conditions and who fit your program criteria).

“We can’t afford Medicare’s fees and audits.” – We’ll discuss costs in Section 6, but note here: enrolling as a Part B practice does not require an upfront fee for physician practices[26]. And while compliance does require effort (and yes, audits happen), many digital health orgs find that participating in Medicare via models like ACCESS is financially viable due to the new revenue stream it opens (Medicare pays consistently, even if rates are lower than some private payers). Also, CMS is providing a new pathway precisely to pay for tech-enabled care that wasn’t reimbursed before, which can be a significant opportunity.

In short, digital health companies can succeed in Medicare – you just need to navigate the enrollment process and follow the rules. Next, we’ll outline everything you must handle once you’re enrolled and preparing to operate under ACCESS: compliance, care standards, billing setup, reporting, and more.

5. After Enrollment: Meeting ACCESS Participation Requirements and Operational Responsibilities

Enrolling in Medicare was the first big step. Now, as a Part B provider aiming to join ACCESS, your organization takes on a set of ongoing responsibilities. This section breaks down what you need to do to stay compliant, deliver care, and get paid under the ACCESS model. Think of it as your operational checklist post-enrollment.

5.1 Regulatory Compliance and Clinical Standards

Being a Medicare provider means upholding quality and compliance standards on multiple fronts:

HIPAA and patient privacy: As a covered entity, you must protect patient health information. Ensure your digital platforms and communication tools are HIPAA-compliant (encrypted, secure logins, etc.). Have Business Associate Agreements with any vendors handling PHI. Breaches can lead to fines, so invest in good IT security and training.

Licensure and scope of practice: Double-check that every clinician is licensed in each state where you will treat patients. Telehealth complicates this: if you enroll in one state but treat patients in others, your providers need those state licenses. Also ensure NPs, PAs, etc., operate under the appropriate supervision or collaboration per state law. Medicare defers to state scope-of-practice laws, so maintain compliance with those. If you plan a multi-state telehealth service, consider the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact to ease physician licensing, and check if any waivers exist for telehealth post-PHE (Public Health Emergency). As far as Medicare enrollment itself, it currently restricts assigning a provider to multiple MAC regions easily (they typically enroll in one “home” MAC)[40], but providers can get privileges in additional states via approval. Work with your MAC if expanding.

Medical Director and clinical oversight: ACCESS requires a Medicare-enrolled physician to serve as the Medical (Clinical) Director[2]. This person is responsible for care oversight and compliance with the model. In practice, your Medical Director should establish clinical protocols, supervise any non-physician clinicians, and ensure the care meets quality standards. They also likely will liaise with CMS for clinical matters. You should have a Medical Director Agreement (even if it’s your CMO) outlining their duties, including monitoring outcomes, ensuring evidence-based care, and reporting any quality issues. Many states require physician oversight for NP/PA care as well; integrate those requirements.

Clinical guidelines and quality of care: Delivering high-quality, evidence-based care is both an ethical and a CMS expectation. ACCESS is outcomes-focused, so hitting those outcome targets (e.g. blood pressure reduction in hypertension) is paramount[41][42]. Adopt or develop clinical practice guidelines for your focus conditions. For example, if you’re tackling diabetes, have standard protocols for medication titration, lifestyle counseling, etc., aligned with ADA guidelines. Document these care pathways. You should also implement continuous quality improvement processes – e.g. track internal metrics like engagement rates, adverse events, patient feedback – to continually refine your program. Remember, CMS will publicly report your aggregate outcomes (risk-adjusted) in the ACCESS participant directory[43][8], so your reputation (and potentially future reimbursement adjustments) will depend on quality results.

Patient rights and protections: Medicare patients have certain protections. For instance, you may need a consent form for model participation clarifying that they’re entering a special program. Patients retain the right to get services outside your organization; you cannot lock them in or induce them to avoid other care if needed. Also, comply with non-discrimination laws (Title VI, ADA, etc.) – make your digital services accessible (e.g. 508 compliance for apps, language access for non-English speakers, accommodations for disabilities). If you’re offering any incentives to patients (like a free device or internet for monitoring), check with legal counsel on Civil Monetary Penalties law exceptions for patient incentives in models.

FDA requirements for digital tools: ACCESS acknowledges that some participants will use software or devices that may be FDA-regulated (e.g. a mobile app that qualifies as a medical device)[44]. Ensure any tool you deploy that requires FDA clearance or approval has it, or that it falls under an enforcement discretion policy. CMS expects participants to meet “applicable FDA requirements (or be under enforcement discretion)”[45]. The model is coordinating with an FDA pilot (TEMPO) for certain unapproved products to gather real-world data. If this applies to you (say you have a novel AI diagnostic), consider applying to that FDA pilot or ensure you have at least a class II clearance if needed.

Fraud and abuse compliance: Establish basic compliance policies to avoid fraud and abuse. Train your staff on Anti-Kickback Statute rules – e.g. you cannot pay physicians purely for referrals. Any arrangement with referral sources must be at fair-market value and properly contracted. Similarly, be mindful of Stark Law if any physician owners refer patients (the ACCESS model might have waivers for certain financial arrangements, but none are announced yet – until then, operate under normal rules). Keep thorough documentation of services provided in case of audit. False claims (billing for things not done or outcomes not achieved) carry heavy penalties, so accuracy is vital.

In summary, run your digital clinic with the same rigor as a brick-and-mortar provider group. Set up a compliance program appropriate to your size (at minimum, designate a compliance officer or champion, even if part-time, to monitor these areas). The investment in compliance will pay off by preventing major issues that could jeopardize your Medicare status.

5.2 Delivering Care Under the ACCESS Model

ACCESS is unique in that it is outcomes-driven and offers flexibility in how you deliver care. But with that comes some requirements to ensure patients receive appropriate services:

Care model and scope: When applying to ACCESS, you’ll choose one or more clinical tracks (e.g. Cardio-metabolic, Musculoskeletal pain, Depression/Anxiety, etc.)[46]. For each patient, you’ll manage their qualifying condition(s) for a 12-month care period. Your care can include virtual visits, remote monitoring, coaching, medication management, digital therapeutics – whatever it takes to improve outcomes[47][48]. CMS gives you freedom here (“deliver modern, technology-supported, patient-centered care”[42][49]), but implicitly, you must provide a reasonable standard of care. This means: initial assessment, personalized care plan, periodic check-ins, medication adjustments if needed, referral to in-person care if complications arise, etc. Develop a care protocol for the year-long intervention and ensure each patient gets the services promised.

Patient onboarding and consent: You will likely need to obtain written consent from beneficiaries to participate in the model (CMS will detail this in the Participation Agreement). This consent will cover that they understand you’ll be paid in a new way and that certain services are included under the model. Make the onboarding user-friendly – perhaps through a digital consent form – but thorough. Educate patients that during the care period, your team is responsible for managing their condition and they should reach out to you for related needs (while still seeing their PCP for general care).

Coordination with other providers: Unlike siloed care, ACCESS stresses coordination with patients’ primary care and any referring clinician. You are required to share care plans and periodic updates with those providers[50][51]. Practically, this means when you start care, you should send the patient’s PCP a care initiation note (CMS will provide a standardized template for this, including your contact info, treatment goals, etc.[52][53]). Similarly, at care completion or significant milestones, send summaries[53][54]. You must use a secure electronic method – acceptable ways include Direct secure messaging, Health Information Exchange (HIE) portals, or possibly FHIR-based exchange[55][56]. The key is to document that you attempted or did share the info. CMS will likely audit this coordination requirement, so set up an internal process: e.g. your EHR auto-faxes or Direct-messages the PCP upon certain events, and you log it. Good coordination not only fulfills requirements but also improves patient care (and PCPs get a small payment for reviewing your updates, incentivizing their engagement).

Patient accessibility and support: You are accountable for helping patients achieve outcomes, so you need to be proactive and accessible. This means offering multiple touchpoints: e.g. a nurse or coach available for questions, an app for daily monitoring, periodic virtual visits with an MD/NP. You might consider a 24/7 support line for urgent issues related to the condition (or at least rapid callbacks). Patient engagement is crucial – drop-offs could hurt outcomes and thus your payments. Also, ensure you meet any CMS-defined minimum service elements. The RFA doesn’t prescribe exactly how often to see patients, but implicitly, if a patient isn’t improving, you should intensify contact. Document all interactions in the medical record.

In-person care contingency: While you may be virtual-first, have a plan if a patient needs in-person services (labs, imaging, procedures, or a physical exam). This could be via partnerships with local labs or advising the patient to see their PCP or a specialist. ACCESS doesn’t forbid participants from ordering or coordinating traditional care; it just doesn’t pay separately for it except through the OAP. So coordinate these needs as part of your care management. If a patient’s condition deteriorates beyond what your model covers, you might trigger a care escalation – e.g. refer to a cardiologist – and per model rules, you’d send a care escalation update to the PCP[53][57]. You might then pause or end the model intervention for that patient if appropriate (CMS hasn’t detailed if early termination is allowed, but presumably if a patient needs out, they can disenroll).

Patient satisfaction and rights: Although ACCESS is outcomes-focused, patient experience will matter. Satisfied patients are more engaged and more likely to complete the program (achieving outcomes). Solicit feedback, address complaints promptly, and provide clear contact information for questions or concerns. Remember that as a Medicare provider, beneficiaries can file complaints about you to the MAC or 1-800-MEDICARE. Handle issues internally to avoid that. If a patient wants to quit the program, have a process to off-board them safely and transition care.

In essence, operate like a high-touch chronic care clinic, albeit virtual. CMS is testing whether this model can improve outcomes, so bring your A-game in care delivery. Strong clinical outcomes and good coordination will not only secure your payments (full OAPs)[58][59] but also build your reputation in the Medicare space.

5.3 Billing and Payment Infrastructure

Even though ACCESS isn’t standard fee-for-service, you still need a robust billing infrastructure because payments flow through Medicare’s claims system. Key components:

Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC): By now you know which MAC region you’re in (e.g. Noridian, Novitas, Palmetto, etc., depending on your practice location). All your Medicare claims – including model-related G-codes – will go to this MAC[60]. Establish an account on the MAC’s provider portal if available, and set up Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) with them or through a clearinghouse. Many startups choose to use a third-party billing service or software to handle claim submission. Ensure that whatever system you use can accommodate the submission of G-codes and any required modifiers for the model.

Innovation Payment Contractor (IPC): CMS mentioned an “Innovation Payment Contractor (IPC)” in model materials[61][62]. This suggests CMS might use a specialized contractor to help process or monitor the model payments, though it’s likely invisible to you (you’ll still submit claims to the MAC). Be aware that some backend reconciliation might occur with another contractor. For your purposes, follow CMS instructions on how to bill model codes, and the payments will be handled appropriately (some might come quarterly via a lump sum rather than individual claims payments, for example).

Billing codes (G-codes): ACCESS will use new HCPCS G-codes to represent the model’s payments and possibly key activities[63][60]. G-codes are often alphanumeric codes starting with “G” that CMS uses for specific programs. For example, there might be a G-code for “ACCESS initial monthly payment” and another for “ACCESS continuation monthly payment” and modifiers for different tracks or outcome tiers[60][64]. These codes are billed like a claim on a CMS-1500 form (or electronic 837P) to your MAC, as if you’re billing a service, except they represent the model payment[60]. CMS has indicated participants will “submit claims for ACCESS services using CMS-defined, model-specific G-codes”[63] on a monthly basis. So, you’ll need to incorporate a monthly billing workflow: e.g. at the end of each month of a patient’s participation, you submit a claim with the G-code for that month (perhaps one per patient).

Expect additional guidance on the exact codes in 2026. The RFA mentions a Co-Management Payment G-code for PCPs (with a modifier) to be shared in 2026[65]. It also mentions that ACCESS G-code spending will be treated like FFS for ACO accounting[66], which is more of a CMS internal note. For you, the action item is: stay updated on the billing codes released (likely via a Model Participant Guide or CMS billing instructions) and ensure your billing system is ready to handle them. These codes might require putting the patient’s condition diagnosis on the claim and maybe some identifier that they’re in ACCESS.

Claims example: Suppose you enroll 100 patients in the hypertension track. Each month, you’ll likely submit 100 claims (one for each patient) with code “GXXX1” (hypothetical code for “ACCESS Hypertension Monthly Payment”) with a charge of $0 (often model claims are submitted with $0 charge and then paid a fixed amount by CMS automatically). The MAC will process these and issue payment (which might be funneled to you quarterly). You might also submit at the end of 12 months a code indicating completion or outcomes measured, etc. The specifics will come from CMS’s model ops guide.

Electronic health record (EHR) and data integration: For billing, you don’t strictly need a full EHR, but you do need something to generate claims. Many digital health startups use an integrated platform or a lightweight EHR (some use an EHR + add custom modules for the model). You might consider systems that are FHIR-enabled, as ACCESS will require outcomes reporting via FHIR API (discussed below). At minimum, have a way to track each patient’s enrollment date, care period, and outcome data, as you’ll need this info when submitting your claims and reports.

Medicare Remittance and accounting: Ensure your finance team or billing vendor can reconcile Medicare payments. When you get paid for these G-codes, you’ll receive remittance advices from the MAC. Verify you’re paid correctly for each patient period. If a patient leaves early or outcome adjustments are made, payments could be prorated or withheld – you need to keep an eye on that. CMS mentioned partial withholds and adjustments based on outcomes[67][68]. Likely, you might get, say, 70% of the payment through monthly claims and 30% is held back and only paid if you meet the outcome at 12 months. Be prepared to track such withholds. The IPC might handle that reconciliation at quarter or year-end.

No patient billing: During active care, you should not bill patients for any co-pays for the model’s covered services (the OAP has no beneficiary cost-sharing). Also, any co-management code the PCP bills is without patient cost-sharing[69][51]. So if patients see an EOB, it should show $0 due from them. Make sure your billing doesn’t accidentally generate statements to patients. Traditional FFS claims outside the model (e.g. unrelated services) would still have the usual 20% co-insurance unless they have Medigap.

MAC liaison: It helps to identify a point of contact at your MAC for enrollment and billing questions. If something odd comes up (like your G-code claims are denied initially because the system isn’t updated), the MAC’s provider relations can assist. Since ACCESS is new, not all MAC staff will be familiar at first – keep CMS’s model team contacts handy as well (they often provide an email for participant questions).

In short, treat the model billing as another revenue cycle management process: set up to submit clean claims, monitor payments, and resolve any denials. The technical lift is not huge (maybe a few custom codes), but the important part is accuracy and compliance (ensuring you only bill what you should, when you should). The good news: no patient collections to chase for these payments, since CMS pays them fully if earned.

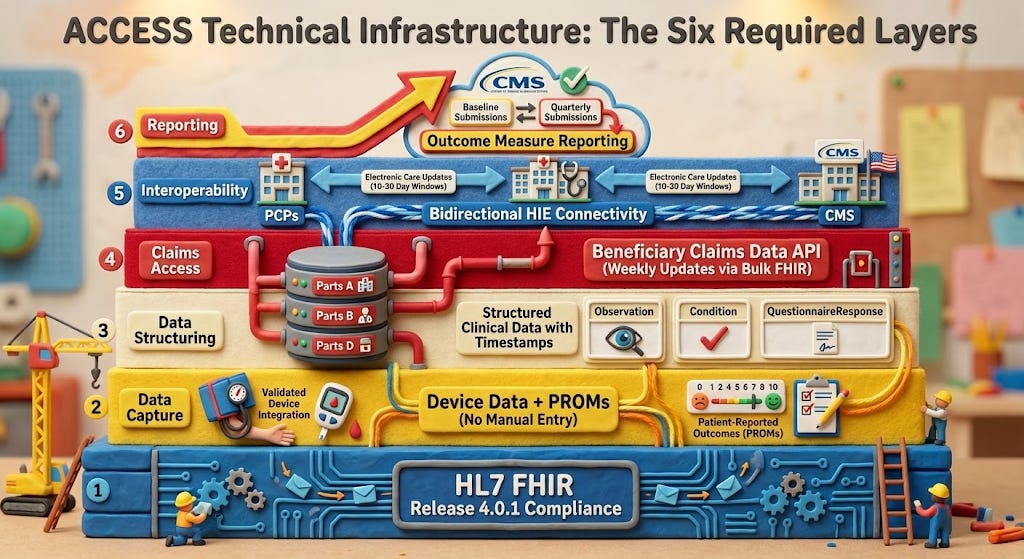

5.4 Outcome Reporting and Data Sharing (FHIR APIs)

A standout feature of ACCESS is the requirement to report clinical outcomes data via FHIR API. This is how CMS will gauge whether you achieved the targets to earn your full payment. Key tasks:

Understand the measures: Each track has specific Outcome-Aligned Payment (OAP) measures (e.g. blood pressure reduction, HbA1c improvement, depression scale improvement). CMS will define these and the baseline vs target for each patient[70][71]. You must capture those measures in your workflow – typically at start (baseline) and periodic or end of care. For example, record a patient’s BP at intake and at 12 months. Some measures might be % of patients above a threshold or average improvement.

FHIR API submission: CMS will provide a FHIR-based Reporting API for you to submit these outcome data[72][73]. FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) is a modern standard for exchanging health data. Likely, you’ll have to transmit a FHIR bundle or resources that include patient identifier, measure results, and some meta-data. This might be required quarterly or at least at the end of each patient’s cycle. The model timeline suggests “Submit OAP Measures data (recurring)” as step 4 in ongoing operations[72].

Technical integration: If you have a tech team, plan early to integrate with CMS’s API. CMS will likely give sandbox/testing details in the model onboarding. Make sure your data systems can export the required FHIR resources. If you’re using a modern EHR or care management platform, talk to your vendor about supporting these specific measure exports. Alternatively, you might choose to manually enter data into a CMS web portal for initial cases if integration is heavy – but given the model’s tech focus, investing in automation is wise, especially as you scale to many patients.

FHIR resources and standards: CMS might use specific profiles for these measures. For example, they might use FHIR Observation resources for vital signs or QuestionnaireResponse for patient-reported outcomes. Ensure your team is familiar with FHIR basics (there are open-source libraries in many programming languages for FHIR). CMS’s Data Exchange: It’s possible the model will align with standardized frameworks like US Core Data for Interoperability or have a custom Implementation Guide. Watch for the technical documentation from CMMI. (This aligns with CMS’s broader push for interoperability and using APIs instead of Excel sheets to collect model data.)

Reporting frequency and accuracy: Whether you report monthly, quarterly, or just at outcome time, mark those dates. Timely reporting is likely tied to payment – e.g. CMS might not release the final outcome-based portion until you send the data. Also, integrity of data is crucial. Submit actual measured values. Be prepared for audits: CMS or the Innovation Contractor may audit medical records to verify that the outcomes you reported match documentation. Misreporting outcomes could be considered a false claim. So if you say a patient’s blood pressure dropped 15 mmHg, ensure you have the readings to back it up.

Other required data submissions: In addition to outcome measures, ACCESS participants will use other APIs:

· An Eligibility API to confirm a beneficiary’s Medicare eligibility in real-time[74] (likely to check they have Part B and aren’t in an HMO, etc. when you enroll them).

· An Alignment API to formally enroll the beneficiary into the model[75].

· A Claims data API (BB or BCDA) to optionally receive their claims history for care coordination[72][76].

· Possibly a Directory API for maintaining your participant profile.

Ensure your technical team is ready to work with these. CMS might provide a bulk solution or portal, but given your startup savvy, using the APIs will likely be more efficient at scale.

· Outcome transparency: CMS will publicly display your aggregate outcomes (e.g. what percentage of your patients hit the targets, risk-adjusted)[43][8]. You won’t directly report that – CMS calculates it from your submitted data – but know that your data accuracy affects your public profile. Good outcomes data submission = good public metrics = more patient referrals potentially.

One way to simplify all this is to leverage any CMS-provided tools or vendors. The RFA mentioned a vendor directory for tools to support participation[77]. There may be companies offering an “ACCESS tech suite” including FHIR reporting, etc. If building in-house, allocate time for development and testing well before you go live.

In summary, data reporting is not an afterthought in ACCESS – it’s central. Integrate outcome capture into your care process (e.g. automatically schedule a final assessment at month 12, etc.) and ensure that data flows to CMS as required. This is how you get paid fully and how CMS judges the success of the model.

5.5 Ongoing Admin: Maintenance, Audits, and Communication

Finally, let’s cover the ongoing administrative overhead once you’re up and running:

Revalidation and updates: Remember to update PECOS if you have changes – new locations, adding/removing an owner, etc. Also, when CMS sends a revalidation request (typically every 5 years), respond promptly via PECOS[6]. Mark your calendar for revalidation due by 5 years from initial approval (or check PECOS which shows revalidation date). Not revalidating = deactivation, which would boot you from the model until reactivated.

MAC and CMS communication: Subscribe to your MAC’s email updates and the CMS ACCESS model listserv. MAC emails will alert on any provider enrollment changes or fraud schemes to watch out for. ACCESS listserv will update on model tweaks or upcoming deadlines. Also attend any CMS Open Door Forums or webinars for ACCESS participants – these often provide clarifications.

Model monitoring and evaluation: Expect that CMS (or an evaluator) might reach out for additional info as part of model evaluation. For example, you might be asked to participate in surveys or interviews about your experience. Cooperate, as these are usually required in the Participation Agreement.

Compliance audits: You should anticipate program integrity audits either by your MAC, a Unified Program Integrity Contractor (UPIC), or CMS auditors. They might audit:

· Medical records to ensure you actually delivered services and outcomes you claimed.

· Enrollment compliance (ensuring no excluded persons involved, etc.).

· Patient outreach practices (to ensure you’re not recruiting patients with incentives beyond what’s allowed).

Have an internal audit file ready: keep copies of patient records, outcome calculation sheets, and correspondence in a well-organized manner. If audited, respond through the proper channels, and consider engaging legal counsel experienced in CMS audits if it’s a complex review.

Financial management: Keep track of the costs of participating – staffing, tech, etc. Why? Because after year 1, you’ll want to evaluate if the model payments cover your costs and margin. CMS plans to potentially adjust payment rates over the 10-year model[67], so staying financially diligent will help you advocate if rates are insufficient. Also, ensure robust accounting controls for Medicare revenue; you might be subject to a federal audit like any healthcare org (and if you receive significant Medicare funds, a single audit under federal grant rules if applicable – though likely not unless also getting grants).

Patient count and scaling: CMS allows rolling application through 2033[78][79]. That means you can grow over time. Just ensure that as you scale, you maintain the standard of care. If you expand to new states or add lines of business, consider whether to enroll new practice locations or even new entities as needed. But preferably, stick to one Medicare enrollment if possible to keep it simple, adding locations to it if needed.

By covering compliance, care delivery, billing, and reporting as above, you will be operating in line with both Medicare rules and the ACCESS model’s special requirements. It’s a lot of responsibility, but breaking it into these domains makes it manageable. Many early-stage companies find that after the initial learning curve, Medicare operations become just another part of their business processes.

6. Costs and Administrative Burden: What to Expect

Enrolling in Medicare and participating in ACCESS is an investment. Here we outline the costs (in dollars, time, and effort) that a digital health startup should anticipate, so you can budget and plan accordingly:

Enrollment costs: The good news: no application fee for physician or practitioner-based organizations[26]. Medicare waived the ~$600+ fee for groups of physicians/non-physicians, so unlike a home health agency or DME supplier, you pay $0 to enroll in Part B. There will, however, be incidental costs like obtaining an NPI (free), perhaps notarizing documents or postage if anything required mailing (minimal). If you use a credentialing service or consultant to help with enrollment, that’s a cost (varies by service). But the enrollment itself is primarily a time cost (gathering info, filling forms). Expect to spend 10–20 hours of staff time for the initial enrollment if you’re doing it carefully yourself.

Staffing and training: Once enrolled, delivering services under Medicare means you may need to bolster your team:

Billing/coding expertise: It’s highly advisable to have a medical biller or billing service familiar with Medicare. Even though ACCESS uses simplified payments, you’ll interact with the Medicare claims system. A billing professional will ensure claims go through and manage any denials. This could be an in-house hire (perhaps a part-time experienced biller at startup phase) or an outsourced RCM service (often charging ~5% of collections or a flat fee). Don’t overlook training your team on Medicare coding and compliance – even your clinicians should know the basics (e.g. what they can/can’t bill during the model). Budget: A part-time biller might be $20–$30/hour; RCM service for a small volume might be $500–$1000/month initially.

Compliance and admin: As you saw, maintaining compliance is continuous. You might assign an existing team member (COO or head of clinical operations) as Compliance Officer. Down the line, if you scale, a dedicated compliance manager may be needed. Also consider legal fees for periodic consultation with a healthcare attorney (particularly around Stark/AKS, or any novel arrangements). Budget: If using outside counsel for setup and periodic check-ins, maybe $10k-$20k per year at startup size. Internal compliance FTE could be a later need.

IT and integration: If you need to develop tech capabilities (FHIR API integration, data reporting pipelines, possibly custom EHR features), that’s an engineering cost. You might allocate a few sprints of developer time to this. If your current platform isn’t up to it, you might invest in a new module or external software. Budget: Could range widely – from using existing tools (maybe minimal extra cost) to building custom (tens of thousands). However, consider that this tech investment also builds your IP and could be reused for other payer contracts that want outcome data.

Clinical staffing: Under ACCESS, you have flexibility in clinician types (physician, NP, RN, coach, etc.). But to meet Medicare requirements, you need at least one physician overseeing (the Medical Director)[27] and likely some NP/PA or RN care managers doing the day-to-day. Plan your care team ratio and its cost. Medicare’s payments have to cover this workforce. For instance, if CMS pays $X per patient per month, ensure your staffing model allows profit. Work out how many patients a care team member can handle. There may also be peak workload at reporting times (analyzing outcomes, submitting data) which might require temporary help or overtime.

Infrastructure and tools:

EHR/care management system: If you’re not already using a certified EHR, you might not strictly need a fully certified one for ACCESS (unless future rules mandate it), but you need a system to document encounters and store data. If you choose an EHR, there are low-cost options (some even free for small practices) or more custom solutions. Also, ensure you can produce the standard CMS claims file or have an EHR with integrated billing module.

API and data systems: As mentioned, setting up the FHIR API might incur cloud costs or integration costs. If CMS requires connection to an HIE or use of a specific API gateway (like using an OAuth2 client for their API), there’s time to set that up. If you decide not to DIY, you might subscribe to a middleware (some companies offer FHIR connectivity as a service).

Hardware and devices: Depending on your model, you may provide patients devices (e.g. BP cuffs, glucometers, wearables). While not directly a Medicare enrollment cost, it’s part of the operational cost of participating. ACCESS payments have to cover these or you may find partnerships (maybe the patient’s insurer covers some devices, etc.). Budget for these per patient, or arrange to use existing patient-owned devices when possible.

Administrative burden and process changes:

Documentation burden: Medicare has a reputation for requiring documentation. ACCESS is a bit different, focusing on outcomes, but you still must keep thorough medical records. That means clinicians need to document clinical assessments, patient consent, care plans, and communications. If your startup was used to a leaner documentation style for say, cash-pay clients, expect to beef it up for Medicare. Training your clinicians on Medicare documentation guidelines (for instance, if you do any E/M visits, ensure they document appropriately even if you’re not billing those in FFS). This is more time spent per encounter on charting, which is a cost (time is money). However, because ACCESS isn’t paying per note, you might find documentation can be more streamlined as long as it supports outcome measurement and coordination.

Monitoring regulations: You’ll need someone to keep up with CMS updates – e.g. annual PFS rule changes might affect telehealth policies that impact you, or model tweaks via sub-regulatory guidance. This is ongoing work, scanning CMS site or attending webinars. It’s wise to join trade groups (like the ATA – American Telemedicine Association – or Digital Medicine Society) as they often summarize relevant changes.

Quality reporting obligations: Besides the model outcomes, ensure you know if you’re subject to any other Medicare reporting, like MIPS (Merit-based Incentive Payment System) for quality. Important: It appears ACCESS may exempt participants from MIPS reporting because you’re in an advanced model (to be confirmed by CMS). If not exempt, and if you’re billing any FFS, you might have to report quality measures under MIPS which is another administrative task. Keep an eye on CMS guidance here.

Audits and corrective actions: If something goes wrong (e.g. a minor compliance breach or an outcome not achieved), you might need to do corrective action plans. This overhead is hard to quantify, but be prepared to allocate leadership time to remedy any issues. For example, if a monitoring audit finds you didn’t send all required PCP updates, you’d need to implement process fixes and report back.

Overall, the administrative burden is moderate but manageable with planning. Many startups have navigated Medicare programs successfully by treating compliance as a part of their quality strategy rather than a hurdle. One particular benefit: no patient billing hassle and reduced bad debt. Medicare will pay you reliably for each aligned patient’s care period, as long as you do your part. That predictability (the “subscription-like” payment)[80][81] is actually a relief versus chasing fee-for-service volume or collections.

Lastly, consider intangible costs: joining a Medicare model may require a culture shift for a startup – more formality in processes, more oversight from external entities. Ensure your team is ready for that. The trade-off is the opportunity to serve potentially thousands of Medicare beneficiaries and prove your outcomes on a big stage, which can be very rewarding (and, if successful, profitable and scalable).

7. Application and Resources: Final Steps to ACCESS Participation

With Medicare enrollment secured and an understanding of obligations, your company’s final step is to formally apply to join the ACCESS model through CMS’s Innovation Center:

Request for Applications (RFA): CMS has released the ACCESS Model RFA[82]. Review it in detail – it outlines eligibility, application questions, and deadlines. As noted in the McDermott+ summary, initial applications are due by April 1, 2026 for the first cohort[83]. The model will accept new participants through 2033 on a rolling basis[78], but earlier start means more opportunity. Ensure you complete the RFA response, which likely includes narrative sections on your care model, team, operational readiness, and perhaps letters of intent from partner physicians (if any).

Medicare enrollment proof: The application will likely require your Medicare CCN/PTAN or other identifier to prove you’re enrolled (or at least that you’ve applied). As highlighted, “Applicants will need to enroll in Medicare Part B prior to executing a participation agreement”[10]. So include evidence – e.g. a copy of your Medicare approval letter or your CMS Certification Number – in the application appendix if requested.

CMS ACCESS Interest form: CMS has provided an Interest Form on their site[84][85]. If you haven’t already, fill that out (it’s not binding, but it puts you on their radar and email list).

Participation Agreement: If CMS approves your application, you’ll sign a formal agreement. This is a contract with CMS governing model participation. Review it carefully (legal counsel recommended). It will incorporate many of the requirements we’ve discussed (e.g. you agree not to bill FFS for those patients, to submit data, to allow evaluation, etc.).