Techy Surgeon Explainer: MAHA Elevate

The Innovation Center's $100M bet on lifestyle medicine is a policy signal...and an operational challenge that health systems can't afford to ignore.

Every so often, CMMI releases a model that feels less like a policy experiment and more like a signal.

MAHA ELEVATE is one of those moments.

What Is MAHA ELEVATE?

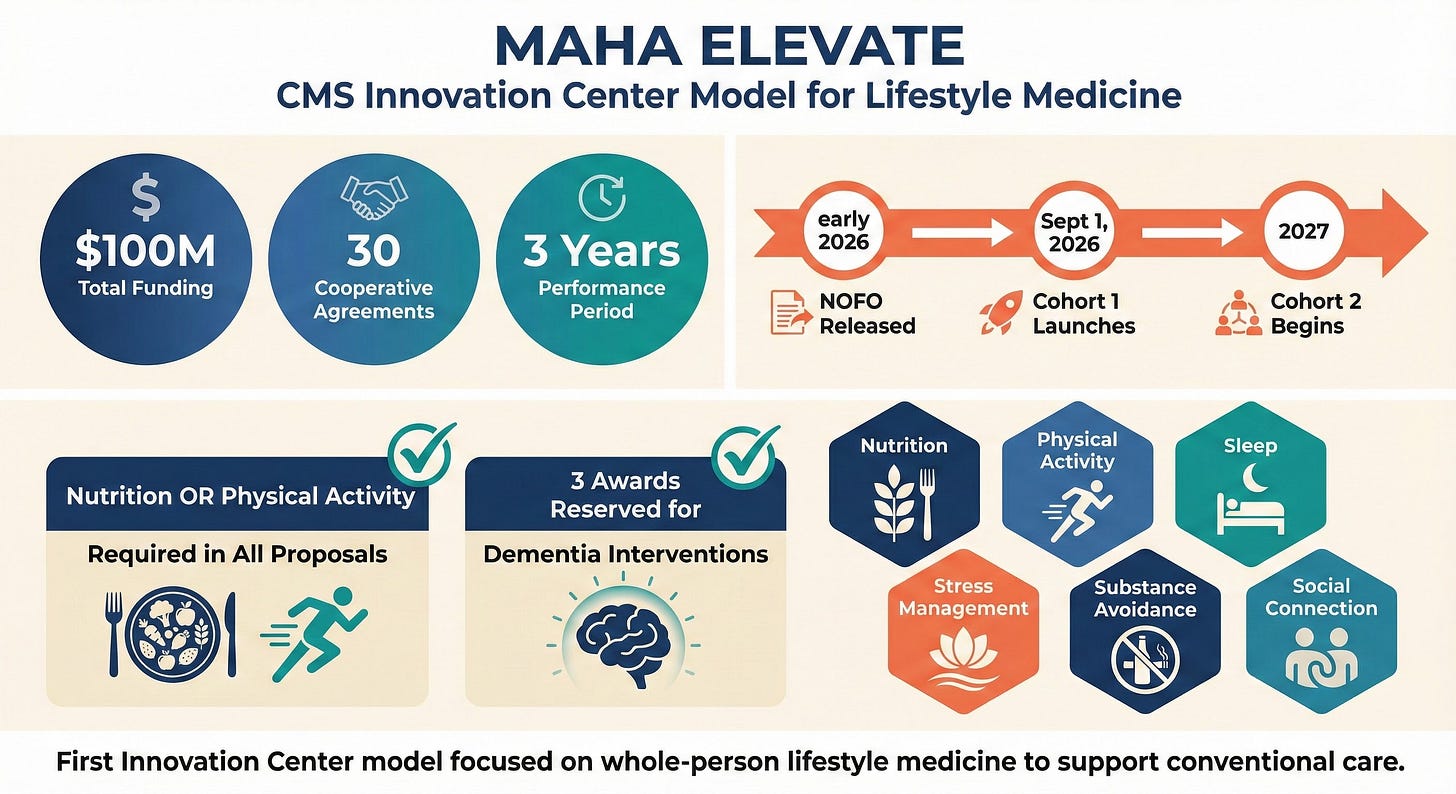

The Make America Healthy Again: Enhancing Lifestyle and Evaluating Value-based Approaches Through Evidence (MAHA ELEVATE) Model is a new CMS Innovation Center initiative designed to test whole-person, lifestyle medicine approaches in Original Medicare.¹ The model will provide approximately $100 million to fund three-year cooperative agreements for up to 30 proposals that promote health and prevention for Medicare beneficiaries.

The details are as follows:

Funding structure. Up to 30 organizations will receive cooperative agreements, with each organization receiving approximately $3 million over a three-year performance period.² The funding can cover whole-person care services that Original Medicare doesn’t currently cover, as well as administration and data collection costs. It cannot be used to cover food or services that can be billed to Original Medicare.¹

Timeline. CMS will release the formal Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) in early 2026. The first cohort launches September 1, 2026, with a second cohort beginning in 2027.¹

Core requirements. All proposals must incorporate nutrition or physical activity as part of their design. This is not optional. Three awards will be specifically reserved for interventions that address dementia.¹

Scope. The interventions are intended to support, not replace, the medical care received by people with Medicare. Participating in a MAHA ELEVATE program does not change a beneficiary’s Medicare benefits, coverage, or rights.¹

Critical focus areas. The model emphasizes six interconnected domains: nutrition, physical activity, sleep, stress management, harmful substance avoidance, and social connection.

This is the first Innovation Center model to focus on proactive, holistic, patient-centered functional or lifestyle medicine approaches to support conventional care.

The Problem CMS Is Trying to Solve

CMS is being unusually explicit about the challenge it’s trying to solve. In 2022, approximately 45% of people with Medicare had four or more chronic conditions, and people with chronic conditions accounted for nearly 90% of total healthcare spending.¹ Our system is quite good at treating downstream consequences of chronic comorbidities…and historically terrible at paying for the work that prevents them.

The evidence supporting prevention has been mounting for some time. The Nurses’ Health Study demonstrated that 80% of all heart disease and over 91% of diabetes in women could be eliminated through a cluster of positive lifestyle practices: healthy body weight, regular physical activity, not smoking, and basic nutritional modifications.³ The American College of Lifestyle Medicine’s position statement is that approximately 80% of chronic diseases and premature deaths could be prevented through lifestyle-related behavior changes.⁴

And yet, Medicare and other insurers have historically not covered the interventions most likely to address the underlying causes of these conditions. Nutrition counseling beyond narrow parameters, intensive behavioral programs, community-based physical activity, sleep hygiene education, stress management, and longitudinal coaching outside clinic walls have largely fallen outside the reimbursement structure.

MAHA ELEVATE is CMS posing a particular question: what if we actually tested whether behavior change, lifestyle medicine, and longitudinal engagement could move outcomes and costs at scale, in real Medicare patients?

Who Can Apply

One of the most interesting features of MAHA ELEVATE is the breadth of organizations CMS is willing to fund.

Eligibility is not limited to health systems or hospitals. MAHA ELEVATE recipients will be organizations that either provide whole-person functional or lifestyle medicine services directly to patients or partner with other organizations to deliver services. Eligible applicants may include:¹

Private medical practices

Health systems and accountable care organizations (ACOs)

Academic organizations

Functional, lifestyle, preventive, and integrative medicine centers

Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics

Community-based organizations

State or local governments

Indian Health Service, Tribal Services, and Urban Indian Programs

Senior living communities

This suggests CMS is increasingly comfortable with the idea that impactful care doesn’t always originate inside hospital walls (something ACCESS should make clear to providers as well), and that technology-enabled, longitudinal programs may be better suited to delivering prevention than episodic office visits ever were.

What Makes a Strong Application

Even without the formal RFP, you can surmise a few things about what will make for a strong application.

A well-defined target population and condition focus. Proposals should target specific chronic conditions with clear intervention logic, not general “wellness.” Every proposal must include a nutrition or physical activity component, and CMS has reserved three awards specifically for dementia-focused interventions.¹

Evidence from prior implementation. Applicants must demonstrate that their interventions are safe and effective for the target population and supported by peer-reviewed literature. CMS is looking for organizations that have already demonstrated success integrating these approaches into conventional medical care with scientifically documented improvements in health.²

Measurement maturity. Applicants must demonstrate experience with data collection or the ability to accurately collect and report all required data from beneficiary enrollees in a timely manner, with appropriate data protections in place.¹ This model exists to generate an evidence base. Functional outcomes, patient-reported measures, engagement metrics, utilization, and cost data will all be critical.

Operational credibility at scale. Recruitment pathways, longitudinal engagement infrastructure, safety monitoring, and delivery outside traditional visits will distinguish competitive applications.

This is not a pilot-for-pilot’s-sake model. CMS wants to learn what actually works and what’s scalable. The findings will inform future Original Medicare coverage determinations and potential future Innovation Center models.¹

The Operational Challenge: High-Touch, Asynchronous Care

Candidly, I think most health systems will struggle with this model.

MAHA ELEVATE rewards longitudinal engagement. It rewards sustained behavior change. It rewards meeting patients where they are, outside the clinic, over time.

Health systems are traditionally terrible at this.

Try calling your doctor’s office. How difficult it is to even get someone on the phone? How often have you booked an appointment and had a 4 month waiting period, or ended up booked at the wrong specialist? Ever try to decode the next step in your care or a loved one’s care plan through your patient portal app? It’s not fun. Now imagine asking that same infrastructure to deliver personalized nutrition coaching, weekly check-ins on physical activity goals, sleep hygiene education, stress management support, and continuous engagement over months or years.

The operational capabilities required for MAHA ELEVATE are fundamentally different from the episodic, visit-centric model that health systems are built around.

This creates a significant opportunity as well as a significant challenge.

The Evidence for Digital Health and Asynchronous Care

The good news: we have substantial evidence that high-touch, asynchronous care models actually work.

Digital rehabilitation is non-inferior to in-person care. A 2024 systematic review found that telerehabilitation resulted in treatment session attendance 8% higher and adherence to exercise programs 9% higher compared to in-person physiotherapy, with equivalent patient satisfaction.⁵ A randomized controlled trial published in npj Digital Medicine demonstrated that a remote digital intervention for chronic low back pain promoted the same levels of recovery as evidence-based in-person physiotherapy, with a significantly lower dropout rate (15.7% vs. 34.3%, p=0.019).⁶

Text-based outreach reduces no-shows and improves engagement. A Cochrane meta-analysis of eight RCTs involving 6,615 participants found that mobile text message reminders improved healthcare appointment attendance by 14% compared to no reminders (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.03-1.26).⁷ One study in a pediatric clinic found text reminders reduced no-show rates from 38.1% to 23.5% in a predominantly low-income population, with the intervention group twice as likely to keep, cancel, or reschedule their appointment after adjusting for confounders.⁸

Remote monitoring improves glycemic control. A 2025 meta-analysis found that remote glucose monitoring significantly improved HbA1c levels compared to usual care (mean difference: -0.35, 95% CI -0.67 to -0.02, p=0.04) and fasting blood glucose (mean difference: -0.82, 95% CI -1.10 to -0.54, p<0.00001).⁹ Patient engagement is the key variable: patients who maintained daily uploads of biometric data were significantly less likely to have poor glycemic control at program end.¹⁰

The challenge isn’t whether these interventions work. It’s that they haven’t been properly reimbursed, and the evidence has largely come from small trials or well-resourced research settings.

MAHA ELEVATE and ACCESS seem to be looking to change that equation.

Why Research-Heavy Organizations Will Have an Advantage

Organizations with established research infrastructure will have a significant advantage in MAHA ELEVATE.

CMS is requiring documented scientific evidence of intervention efficacy. They want data showing outcomes from prior program implementation. They expect rigorous measurement and reporting.

Academic medical centers, research-focused ACOs, and organizations with track records of publishing peer-reviewed outcomes data will be better positioned to meet these requirements.

At Duke, we’ve invested heavily in innovative care models that prioritize longitudinal engagement with musculoskeletal patients. Our Joint Health Program combines sleep hygiene, cognitive behavioral therapy, weight management, and a primary osteoarthritis provider model where the primary provider is a physical therapist, representing a new approach for patients with joint pain. Our Spine Health Program champions chiropractors and physical therapists delivering evidence-based, guideline-concordant care.

These are exactly the kinds of programs MAHA ELEVATE is designed to test.

But the evidence will benefit everyone. Thirty organizations with $100 million is a substantial investment. The findings will inform future Medicare coverage determinations and shape how we think about prevention in the years ahead.

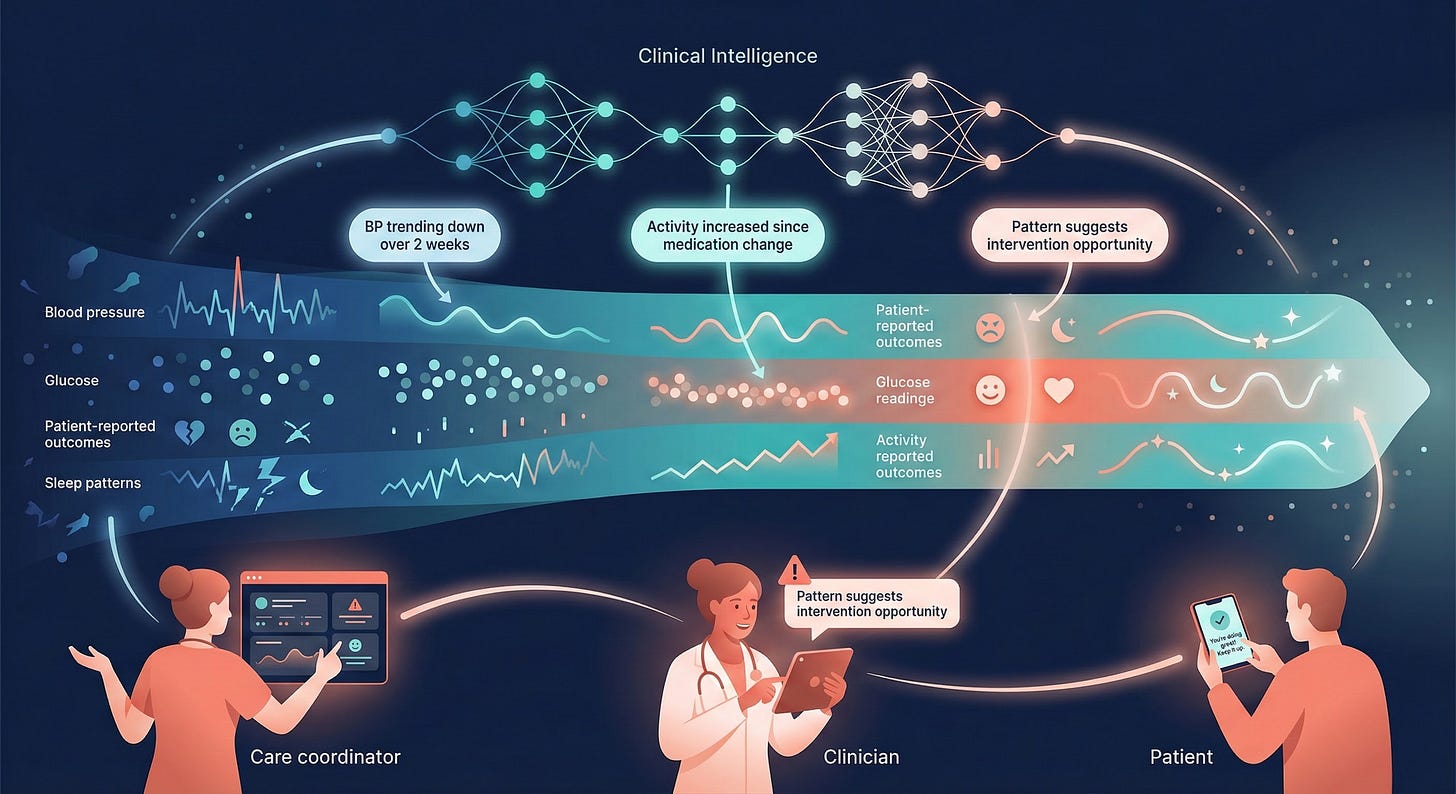

The AI Opportunity: Contextualizing Data at Scale

Longitudinal lifestyle interventions generate enormous amounts of data: blood pressure trends, glucose readings, patient-reported outcomes, activity levels, sleep patterns, engagement metrics. The challenge isn’t collecting this data. It’s contextualizing it and separating noise from signal.

Large language models are uniquely positioned to solve this problem.

Recent systematic reviews confirm that LLMs demonstrate significant potential in chronic disease management, with pooled accuracy rates around 71% for health recommendations, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) enhanced models showing even higher accuracy (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.83-4.58).¹¹ LLMs can translate jargon-heavy medical information into accessible language, provide personalized lifestyle recommendations, offer emotional support, and integrate with wearables and health management applications for continuous monitoring.¹²

Imagine an AI agent that reviews a patient’s blood pressure trends over the past two weeks, identifies patterns the patient and care coordinator might miss, contextualizes the data against the patient’s medication schedule, dietary logs, and activity levels, generates a personalized summary explaining what’s happening and what to try next, and flags concerning patterns for clinical review.

The technical capabilities exist today to make that scenario a reality.

What’s been missing is the incentive structure to deploy them.

Health systems have been understandably risk-averse about automated response generation or autonomous patient companions. Organizations have been cautious about text-based patient outreach, allowing patients to engage with AI tools trained on guideline-concordant content, or deploying small agents that can communicate with patients on defined protocols.

MAHA ELEVATE creates the conditions for this hesitancy to dissipate.

When CMS is funding longitudinal lifestyle interventions and demanding rigorous outcomes measurement, organizations will need scalable infrastructure to deliver high-touch care to hundreds or thousands of patients simultaneously. Human care coordinators alone can’t scale to that requirement. AI augmentation will be less of a luxury and increasingly a necessity.

A Paradigm Shift in How Care Is Delivered

I don’t think this is a one-off grant program. It’s part of a broader and quite sudden shift in how CMS believes care should be delivered. The emphasis on outcome-based reimbursement rather than volume, high-touch patient engagement rather than episodic visits, asynchronous care delivery rather than in-person encounters, digital health platforms rather than traditional clinical infrastructure, and prevention and behavior change rather than treatment of established disease represents a direction of travel that extends far beyond this single model.

Organizations hesitant to participate in MAHA ELEVATE will be admitting something important: that they cannot adapt to this shift. And that’s a problem, because this shift is coming regardless.

CMS aims to have all Medicare and most Medicaid beneficiaries in value-based accountable care by 2030.⁴ The agencies funding healthcare increasingly believe that longitudinal engagement, lifestyle medicine, and technology-enabled care can meaningfully improve outcomes at lower cost.

Organizations that can’t deliver high-touch, asynchronous, outcome-oriented care will find themselves increasingly misaligned with payer expectations.

What I’m Watching For

The NOFO drops early 2026. Here’s what I’ll be paying attention to:

Application requirements. How much flexibility will CMS provide on intervention design? How prescriptive will they be about measurement frameworks?

Evaluation criteria. Will CMS prioritize organizations with existing research track records, or will they fund innovative newcomers? How will they balance reach versus rigor?

Technology expectations. Will digital health infrastructure be explicitly required, encouraged, or simply tolerated? Will CMS provide guidance on AI and automation in patient engagement?

Social drivers of health integration. MAHA ELEVATE emphasizes whole-person care. How will social care needs like food access, housing stability, and social connection factor into application scoring, if at all? one criticism of the wearable and wellness industry is that it is historically left behind the patients who need these interventions most. I am hopeful that Maha Elevate and Access will address this gap.

The Bottom Line

MAHA ELEVATE is a significant policy signal.

For organizations committed to prevention, lifestyle medicine, and longitudinal patient engagement, this is an opportunity to test innovative care models with meaningful funding and generate evidence that could reshape Medicare coverage for years to come.

For organizations still operating purely in episodic, visit-centric models, this is a warning sign. CMS is increasingly willing to pay not just for doing more, but for helping patients stay well, if you can prove it.

And for those of us who believe that thoughtful, evidence-based, technology-enabled prevention can meaningfully improve outcomes?

That’s a door worth walking through.

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. MAHA ELEVATE (Make America Healthy Again: Enhancing Lifestyle and Evaluating Value-based Approaches Through Evidence) Model. CMS Innovation Center. Published December 2025. Accessed December 2025. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/maha-elevate

CMS launches ‘MAHA Elevate’ to test lifestyle medicine in Medicare. Becker’s Hospital Review. December 11, 2025.

Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(1):16-22.

American College of Lifestyle Medicine. Lifestyle Medicine as a Framework for High-Value Care: A Position Statement From the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2024.

Cox AO, Piva SR, Glendenning A, et al. Real-time video telerehabilitation shows comparable satisfaction and similar or better attendance and adherence compared with in-person physiotherapy: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2024;70(3):197-205.

Areias AC, Parreira P, Costa F, et al. Randomized-controlled trial assessing a digital care program versus conventional physiotherapy for chronic low back pain. NPJ Digit Med. 2023;6(1):121.

Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Atun R, Car J. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD007458.

Shah NR, Rareshide CAL, Ganda N, et al. Text Message Reminders Increase Appointment Adherence in a Pediatric Clinic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Pediatr. 2016;2016:4093581.

Odutola PO, Olorunyomi PO, Olatawura OO, et al. Effectiveness of Remote Glucose Monitoring Versus Conventional Care in Diabetes Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine Advances. 2025;3(1):28-36.

Su D, Michaud TL, Estabrooks P, et al. Diabetes Management Through Remote Patient Monitoring: The Importance of Patient Activation and Engagement with the Technology. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(10):952-959.

Wang Y, Chen Q, Zhang L, et al. Unveiling the Potential of Large Language Models in Transforming Chronic Disease Management: Mixed Methods Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e70535.

Busch F, Adams LC, Kather JN, et al. Current applications and challenges in large language models for patient care: a systematic review. Commun Med. 2024;4:170.

Ho AH, Chen IY, King AP, et al. Large language models in patient education: a scoping review of applications in medicine. Front Med. 2024;11:1477898.